by Art Horne

It’s clear that good glute function and strength underpins good knee health – especially in the basketball athlete. However, despite the loads of research from the likes of Powers and Ireland supporting this concept, many athletes still continue to suffer despite our best efforts to strengthen the hip musculature and specifically the Gluteus Medius (GM).

Let’s take a closer look at what may be missing from your current GM training.

The Janda Approach

Janda identified two groups of muscles based on function within both the upper and lower body and classified them as either “tonic” or “phasic”. The tonic group of muscles consists of the “flexors”, while the “phasic” muscle group consists of the “extensors” and work eccentrically against gravity. Because of their position and function, Janda noted that the tonic muscles are prone to tightness and shortness while the phasic muscles are prone to weakness and inhibition.

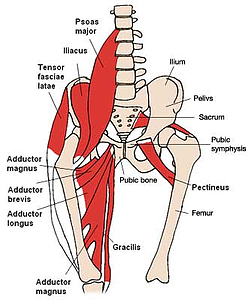

With regards to knee pain, this concept is well regarded and accepted when dealing specifically with the iliopsoas and gluteus maximus among basketball strength coaches and athletic trainers. Not only is the iliopsoas short and tight in most basketball athletes, and the gluteus maximus inhibited, but it is also well accepted that this iliopsoas “tightness” causes a reflexive reciprocal inhibition and thus may be a contributing cause to the phasic nature of the gluteus maximus. In fact, one could spend an extraordinary amount of time “facilitating” the gluteus maximus with retraining or activation exercises, but until the iliopsoas’ tonic nature is reduced these exercises may very well be futile. This is similar to the light switch in your home office. You can flick your office light switch on and off all you want (activation), but unless there is electricity getting to that switch (reduced tone in the iliopsoas) those lights just aren’t coming on.

Flexor Withdrawal Reflex

Definition: a common reflex consisting of a widespread contraction of the physiologic flexor muscles and relaxation of physiologic extensor muscles; characterized by an abrupt withdrawal of the body part in a response to a painful stimuli.

I first learned about this reflex in school where I memorized it for the exam and soon forgot about it until this “phenomenon” was discussed again upon visiting Nico Berg (speaker at the 1st Annual Boston Hockey Summit) in Vancouver BC Canada during a summer learning trip. During my visit he so kindly pointed out to me that after injury, not just after touching a hot stove as we were all taught, that the body undergoes this flexion “contracture”. Take for example the common ankle sprain – extension of the ankle (dorsiflexion) is never the position that an athlete will choose to splint themselves in after injury. Plantar flexion is the preferred motion and thus a loss of Achilles length is the normal consequence of crutch walking after ankle sprain. Yes, gravity has a lot to do with the foot flopping down into this prolonged plantar flexed position, and of course the sheets on your bed further aggravates this problem as you lay helpless against the power of your cotton comforter and gravity, but neither of these can be associated with the flexion “contracture” found in both the knee and elbow after injury. When was the last time you heard an athlete having trouble getting their flexion back after knee surgery?

Let’s take a look how this flexion pattern may relate to knee pain, adductor tightness and ultimately glute med dysfunction.

In this case some would argue that the chicken came before the egg when it comes to PFPS (patellofemoral pain syndrome – or good ol’ fashion knee pain) and associated glute med weakness. For this argument, let’s just say that the knee pain, and hence the painful stimuli, happened first. As we mentioned before the body will undergo a “flexion” contracture or flexion type pattern. Normally, when discussing flexion at the knee the most common sagittal plane flexion-extension movement comes to mind, but for the sake of this argument let’s instead focus on the frontal plane “flexion” pattern.

“But Art, that’s called adduction!”

Call it what you want – but we would all agree that the knee and the surrounding musculature moves and shortens towards the body’s midline – (hip adduction, femur internal rotation and flexion – some actually call this combined motion pronation, but that’s for another day) - think fetal position.

Needless to say, the adductor group similar to your gastroc-soleus complex after an ankle sprain, hamstrings after a knee injury and biceps after elbow insult, become short - agreed?

Enter Sherrington’s law of reciprocal inhibition (Sherrington, 1907), which states that a hypertonic antagonist muscle may be reflexively inhibiting its agonist! Therefore, in the case of our glute med strengthening exercises, the presence of these tight and/or shortened adductors (antagonistic muscles), restoring normal muscle tone and/or muscle length must be addressed first before attempting to strengthen the weakened or inhibited gluteus medius (agonist muscles). (Page)

“Wait a second, I’ve heard this before.”

Yes, you probably have. In fact, Janda so famously described this trend as the Lower Crossed Syndrome. Unfortunately, so much attention has been given to the interplay between psoas tightness and gluteus max dysfunction that I think we’ve forgotten about max’s little brother medius.

Same challenges, same solutions.

Tightness and on one side of the joint with inhibition on the other.

Putting It All Together

My challenge is simply to take this concept (that you are already employing with the hip flexor and gluteus max) one step further and apply to the tonic Hip ADDuctors and the Gluteus Medius – two muscles that sit on opposite sides of the joint similar to the iliopsoas and gluteus maximus.

Taking the tone out of the Adductor Group

Prior to beginning any gluteus medius strengthening work, encourage your athletes to address the soft tissue restrictions within the adductor group with one or both of the below foam roller techniques and follow up with a kneeling hip adductor stretch.

Remember, frantically flicking the light switch on and off won’t get electricity to the light bulb unless power is running into your house first.

Encourage your athletes to address the entire adductor group from origin to insertion. For shorter athletes this is easy by having them "unload" their weight as needed and addressing on a treatment table. Taller athletes often need a taller table or some additional coaching.

For those athletes that need additional help, some light over-pressure from a coach or athletic trainer while taking their femur through their available internal and external range of motion is often helpful. Warning: Athletes with existing knee pain tend to be very tender over the adductor group as it crosses the knee - especially the first time. As this "tone" and discomfort becomes less, so does the athlete's anterior knee pain. In fact, it is my experience that you can predict which athletes have anterior knee pain and which leg their knee pain exists by the amount of tenderness athletes describe during this maneuver.

Follow up your foam rolling with some adductor stretches in an effort to sustain this new tissue quality and length.

References

Beckman SM, Buchanan TS. “Ankle inversion injury and hypermobility: Effect on hip and ankle muscle electromyography onset latency.” Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995; 76(12):1138-1143.

Biel A. Trail Guide to the Body. 3rd Ed. Boulder, CO: Books of Discovery; 2005.

Distefano LJ, et al. “Gluteal Muscle Activation During Common Therapeutic Exercises.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2009. Vol. 39. No. 7. 532-540.

Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s Anatomy for Students. 1st Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

Fredericson M, Cookingham CL, Chaudharis AM, Dowdell BC, Oestreicher N, Sahrmann SA. “Hip abductor weakness in distance runners with iliotibial band syndrome.” Clin J Sports Med. 2000; 10:169-175.

Friel K, McLean N, Myers C, Caceres. “Ipsilateral hip abductor weakness after inversion ankle sprain.” J Athl Train. 2006; 41(1):74-78.

Henriksen M, Aaboe J, Simonsen EB, Alkjaer T, Bliddal H. “Experimentally reduced hip abductor function during walking: Implications for knee joint loads.” J Biomech. Accepted March 11, 2009, not yet in print.

Ireland ML, Wilson JD, Ballantyne BT, Davis IM. “Hip Strength in females with and without patellofemoral pain.” J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003. 33(11):671-6.

Janda V. 1987. “Muscles and motor control in low back pain: Assessment and management.” In Twomey LT(Ed.) Physical therapy of the low back. Churchill Livingstone: New York. Pg. 253-278.

Khaund R, Flynn SH. “Illiotibial Band Syndrome: A Common Source of Knee Pain.” Am Fam Physician. 2005; 71(8):1545-1550.

Nadler SF, Malanga GA, Feinberg JH, Prybicien M, Stitik TP, DePrince M. “Relationship between hip muscle imbalance and occurrence of low back pain in collegiate athletes: a prospective study.” Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001; 80(8):572-577.

Nakagawa TH, Muniz TB, Marche Baldon RM, Maciel CD, Menezes Reiff RD, Serrao FV. “The effect of additional strengthening of hip abductor and lateral rotator muscles in patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled pilot study.” Clin Rehabil. 2008; 22: 1051-1060.

Nelson-Wong E, Gregory DE, Winter DA, Callaghan JP. “Gluteus medius muscle activation patterns as a predictor of low back pain during standing.” Clin Biomech. 2008; 23:545-553.

Page, P. Frank C. The Janda Approach to Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain.

Presswood L, Cronin J, Keogh JWL, Whatman C. “Gluteus Medius: Applied Anatomy, Dysfunction, Assessment, and Progressive Strengthening.” Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2008; 30(5): 41-53.

Sahrmann. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes.

Sherrington CS. 1907. “On reciprocal innervations of antagonistic muscles.” Proc R Soc Lond [Biol] 79B:337.

Shimokochi Y, Shultz SJ. “Mechanisms of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury.” J Athl Train. 2008; 43(4):396-408.

Souza RB, Draper CE, Fredericson M. Powers CM. “Femur Rotation and Patellofemoral Joint Kinematics: A Weight-Bearing Magnetic Resonance Imaging Analysis.” Journal of Orthopedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2010. Vol 40:5. 277-285.

Starky C, Ryan J. Evaluation of Orthopedic and Athletic Injuries. 2nd Ed. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company; 2002.

Umphred DA, Byl N, Lazaro RT, Roller M. 2001. “Interventions for neurological disabilities.” In Neurological Rehabilitation (Umphred DA, ed) 4th ed. Mosby: St. Louis. 56-134.

Wilson E. “Core Stability: Assessment and Functional Anatomy of the Hip Abductors.” Strength Cond J. 2005; 27(2):21-23.