by Steve Scalzi

Coaching the game of basketball simply by “feel” is obsolete. Across today’s coaching landscape, there are numerous resources available to shape your methods of attack for personnel, developmental and strategic decisions. Whether utilizing free resources such as Statsheet.com or subscription services such as Synergy, it is reasonable to expect various coaching decisions be backed by one of three justifications: numbers (the old fashioned points per game, win/loss records, streaks etc.), statistics (analytics such as floor percentage, plus/minus, points per possession etc.) and video (game and/or practice film spliced appropriately). Making a point in a coaching meeting without one of these three is modern day basketball blasphemy. The evidence and resources that are mere clicks away can cut through varying opinions on the coaching staff and move closer to a consensus, provide a player an honest portrait of themselves, and spark innovation to play to your strengths and address weaknesses.

This off-season, I took it upon myself to re-watch every single offensive possession from the 2011-2012 season. The reason was two-fold. From an X and O’s perspective – 1.are we using the best parts of each other through our designed offensive schemes? And 2. in what areas of each player’s game do there exist development opportunities?

After watching 2,293 offensive possessions, opinions are formed or revised. If what you see is contrary to prior perceptions, then presenting a suggestion to the coaching staff, designing on-court or strength training programs for a player requires the evidence from which they’re devised. But asking players, coaches, or strength coaches to sit through 31 games is unrealistic. In order to deliver your findings, they must be clear, concise, and cogent in an easily understood format.

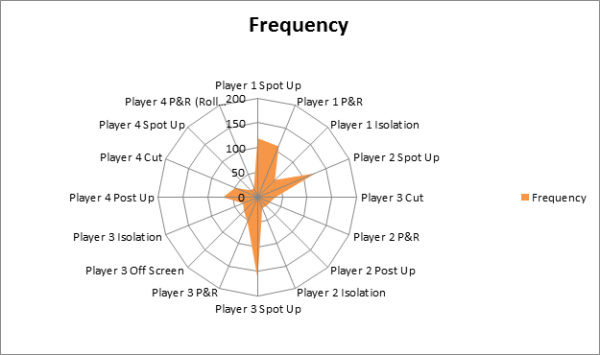

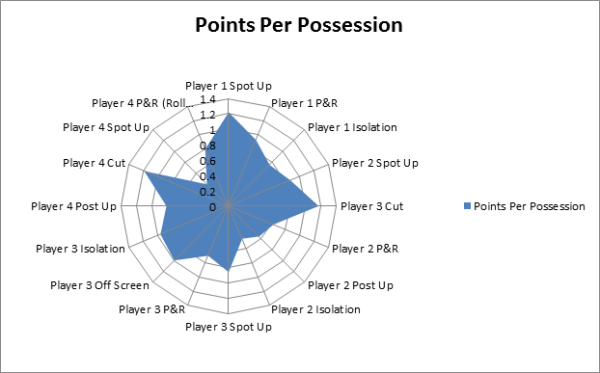

For our coaches, I resorted to radar graphs. I created visual representations of offensive actions - their success rates and their frequency. Synergy identifies every offensive possession outcome. I focused on each action/possession outcome that occurred a minimum of 20 times through our 31 games.

NOTE: by offensive outcome I mean both possession result (i.e. pull up jumper, scoring off a pick and roll) and the specific player who ultimately used that possession. Focusing on deliberate offensive choices, I left out transition possessions and offensive rebounds, whose frequency may have more to do with opportunity than deliberate design.

The radar graphs attached show two different pieces of information for each outcome – points per possession (the scoring outcome Northeastern netted on average) and the total number of times it occurred this season.

Coaching by "feel" originally had me believing that Player 3 was not a great isolation player. He wasn't used very frequently in isolations – meaning we didn't resort to them often, and we didn't do it by design either. But his ratio of frequency to effectiveness was surprisingly good. He was far better than Player 2 in a ball screen and Player 4 taking a short jump shot (things we DID have in our offense deliberately and by design).

This doesn’t necessarily require we suddenly use him in all isolation scenarios and clear out his teammates. Watching our practices with minimal basketball experience will tell you Player 3 can get out of control and thereby less effective. He would even admit so himself. But it’s on us as coaches to review the Synergy clips associated with his isolations that result in positive and negative outcomes.

The moves in which he failed, he failed convincingly – validating our “feel.” Yes, if Player 3 tries to take you off the dribble from the top down, with no ball movement or player movement, things could get dicey.

However, in what Synergy defined as successful isolations, themes emerged. His moves were compact with economy of motion to his footwork and his attack. When the ball was swung side to side and his defender was forced into a closeout, he looked like a pro! One and two dribble moves that were both high level and mature.

From a strength and conditioning perspective, Player 3 was simply at a stage in his career where his foot speed, core strength, elevation, and quick release combined to create a surprisingly efficient athletic move when the game called for it. More of these designed into our offense is more responsible (a wiser investment if you will) than designing post-ups for Player 2 (a tall and talented freshman) at this juncture in their respective development.

Taking a deeper look at Player 2 revealed its own world of information and images as well. As a freshman, he simply was not physically defined enough to establish a post-up game and not yet great at aggressively slashing to the rim in isolations. Here is where "feel" comes into play. What was missing in his game? What moves would you add? How much increased explosiveness can combine with an improved skill set in his next three years? Reviewing his clips I would say he lacked the ability to get low and explosive. He can cover ground with length, but where is the first step? It’s time to collaborate with our strength coach. It is clear he has got work to do in the weight room.

I’m always intrigued by the science of the game. Using modern resources at our disposal provide avenues for us to creatively relay what we’ve learned and to maximize efficiency. Often times, conflicts arise with what our initial “feel” for the game may say. Numbers, statistics, and video are getting easier and easier to find. Interpreting what they reveal and collaborating with coaches, players, and strength coaches to address what’s been discovered is the responsibility of today’s modern coach.