By Ray Eady, M.Ed, CSCS, PES

It's simple, female basketball players need to get strong!

It's not uncommon to hear the following from players after a long competitive season, "Coach, what can I do to..."

1. Jump higher?

2. Improve my jump shot?

3. Play better defense? (defensive stance)

4. Run faster?

5. Move quicker?

6. Etc., Etc., Etc.

My response is usually, "Get stronger!"

Likewise, coaches often approach me stating, "We need to..?

1. Get more athletic!

2. Play better defense! (defensive stance)

3. Run faster!

4. Move quicker!

5. Get in better condition!

6. Etc., Etc., Etc.

My response is usually, "Coach, let's continue to get stronger!"

Let's be honest, today's athletes are consistently looking for a quick fix. Most want to get better at playing their sport but very few are willing to do the things that can really improve their game. When a player asks me what they can do to improve their athleticism, I simply tell them to get stronger. Of course, a well-designed training program is going to include soft tissue work, mobility work, core work, speed work, plyometrics, explosive training, corrective exercises, and other forms of training to enhance athleticism. However, for the purpose of this article, I want to talk about the importance of building pure strength.

I work with the women's basketball team at the University of Wisconsin and every off-season my goal is to get our team stronger than the previous year. Why? Because if there is one physical attribute that a female basketball player needs more than any other it's strength. On the other hand, I am still amazed that some basketball coaches continue to underestimate the importance of strength.

I was talking with a strength coach who was frustrated at his head coach because she wants her players to run during the post-season. The reason; "We need to get in better condition". I do not profess to have all the answers but why do players need to be in "basketball" shape in April, May or June for that matter? Official basketball practice does not start until mid-October. I'll be honest; I am not a fan of players running or conditioning in the post-season. I believe the post-season is a time to heal from the long competitive season and for preparing your athletes for off-season training. The last thing basketball players need in the off-season is pre-season style conditioning. However, basketball players do need lots of strength work and this especially holds true for female athletes.

The myths surrounding females and strength training are quite disturbing and in some cases have negatively impacted our ability to train women despite the tremendous amount of research on the topic. These myths include:

1. Women can't get strong

2. Strength training will make women look bulky and masculine

3. Women should avoid high-intensity training or high-load training

4. Women should train differently than men

5. Women only need to do cardio and if they decide to lift weights, they should be very light.

As strength and conditioning professionals, it is imperative that we educate our coaches and athletes on the benefits of strength training, particularly when dealing with female athletes. This is extremely important when we are introduced to new recruits (freshmen) with limited strength training experiences.

Some people will argue what exactly is strength? Is a female capable of performing a 20-rep squat at 60 percent of their one-rep max a form of strength? Or is a female capable of squatting 1.5 times her bodyweight a form of strength? I would say both scenarios are examples of strength (strength endurance versus maximal strength).

However, the basis of this article is to discuss maximal strength development of which female athletes don't do enough of. Now don't get me wrong, I understand the importance of movement and function and I don't see the world through the hole of a 45-pound plate (a great article posted previously on this blog). However, it's okay to challenge and encourage your female players to lift heavier weights during a training session to develop the strength needed to effectively compete in their sport.

As quoted by Lou Schuler in his book entitled The New Rules of Lifting for Women, "results come from hard work and hard work occasionally includes lifting heavier weights." Basically, it's alright for females (if capable and taught proficiently) to squat heavy, deadlift heavy, perform chin-ups/pull-ups, perform sled work, perform kettlebell work and the list goes on!

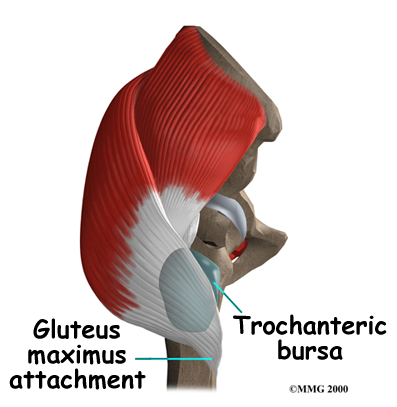

So what are the benefits for getting strong? (I am sure this comes to no surprise for those reading this article.) First and foremost, we all know that female athletes are more prone to sport-related injuries when compared to male athletes. Therefore, the stronger females can become, the less likely they will get injured. Second, strength is the foundation for improving movement efficiency, central nervous system efficiency, balance, coordination, stability, power, speed, elasticity, acceleration, deceleration, quickness, reaction, and conditioning.

Basically, strength is one of the catalysts for enhancing athleticism. Athleticism is the catalyst for providing a solid foundation for developing a skill. Therefore, if you want to improve your ability to post up a defender - get strong; if you want to improve your rebounding capabilities - get strong; if you want to improve your ability to play man-to-man defense - get strong; if you want to improve your ability to absorb contact when driving to the basket - get strong; if you want to set hard screens or get through screens - get strong, if you want to improve your jump shot - get strong! I think you get the point!

Third, all basketball players need to play at an optimal weight/body composition regardless of position. Researchers found that unlike men, women typically don't gain size from strength training, because compared to men; women have 10 to 30 times less of the hormones that cause muscle hypertrophy. So, lifting heavier weights will develop functional strength without the expense of adding unwanted size.

I believe there is also a psychological benefit for females when developing strength. When a female athlete becomes stronger, they become more confident and their self-esteem soars through the roof. Confidence translates into toughness. Toughness is an attribute that is needed to win games. Why, because you need toughness to play defense, to dive on the floor for loose balls, to make free throws, to run your offensive sets, to erase a ten point deficit or to maintain a 10-point lead.

Within a team environment, getting stronger can foster team unity and enhance team toughness simply by having players push themselves (and each other) in the weight room. Make no mistake, female athletes want to be challenged and in most cases; in the same manner as a male athlete. They want to train in an intense and competitive environment and some relish the experience.

Lastly, studies have shown that strength training (strength work) reduced depression symptoms and anxiety levels more successfully than standard counseling sessions. Newly released studies show that after a strength training session, endorphin levels (feel good hormones) are increased by more than 60 percent leaving you feeling rejuvenated and even euphoric, keeping your mind trouble-free.

Mentally, players have to prepare for a long season which can be quite stressful. Players are under extreme stress because of classes, study sessions, and practices. Games are normally played on Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays and during winter break sessions. Social activities with friends and family are at a minimal. If you ever been to Madison, Wisconsin the cold weather and snow can sometimes make life miserable. Let's not forget, losing streaks are stressful as well. Stress can make or break a season! Weight training can be quite therapeutic.

So remember, if you want your female players to be athletic, lean, competitive, self-confident, tough and stress free; lift some heavy stuff once in awhile!