Articles & Resources

Squat - How To Build A Bigger Squat by Jay DeMayo

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Sep 21, 2010 8:24:00 PM

Topics: Strength Training, Jay DeMayo

Core Stability and Basketball Training by Brian McCormick

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Sep 21, 2010 8:23:00 PM

by Brian McCormick

During a high school all-star training camp last weekend in Los Angeles, Draft Express’ Jonathan Givony tweeted about the players’ inability to hold basic yoga positions. He further blamed these athletes’ weak core strength and commented about his disbelief.

Givony used one of the buzzwords of the training industry: core strength or core stability. There are some basketball trainers who appear to train players strictly for improved core strength (though with no real measure of improved core strength or what it means).

When I spent time at the IMG Academy, I never saw a basketball player perform a power-related lift. Instead, every instruction involved imagining the core or tightening the core or doing something to the core. Givony spends a lot of time watching professional trainers, so I imagine he has picked up on this idea, and its apparent importance to basketball success.

When Givony tweeted about his disbelief, I questioned him. Why should we assume that someone who has likely never performed a yoga pose should be able to perform a pose correctly within seconds or even minutes? If I brought a group of yoga practitioners on the basketball court and asked them to shoot three-pointers, should I be surprised if they were unable to shoot correctly within a few repetitions?

Further, the average elite high school basketball player is growing rapidly which creates a loss of coordination and strength, as the bones grow faster than the muscles. Most fast-growing teenagers illustrate some awkwardness, which is why players such as LeBron James who grew quickly and never appeared to go through the awkward stage are the outliers. Therefore, the inability to execute yoga poses does not equate with a lack of core strength, regardless of one’s definition of core strength, but instead is testament to the skill involved in learning different poses, especially for long-limbed basketball players.

While core strength is the magic elixir of the training world (and not just basketball trainers), another basketball trainer said that he “pukes in his mouth” when a client tells him that he needs core training. This trainer identifies skill deficiencies and the underlying movements of the skills and creates an exercise program that improves these movements and ultimately the skills. While some of the exercises cross over between his training and the core strength trainers’ training, his focus often differs.

When I worked as a personal trainer this summer, I saw many people do a typical abdominal exercise where you do a sit-up and throw a medicine ball. Most people do a full sit-up and throw the ball to their partner or at the wall at the top of the sit-up using mostly the chest and arms to throw the ball; they wait for the ball to rebound to them and then return to the bottom.

When I do this exercise, the entire purpose is different. This is not a sit-up and throw, but an overhead throw from a supine position (lying on one’s back). My focus is not to contract my abdominals for the entirety of the exercise, as I heard several people explain to each other at the gym, but to contract forcefully at the beginning of the movement to initiate the throw. I do not do a full sit-up because I am not doing sit-ups: I am throwing the ball against the wall as forcefully as possible. In the process of throwing the ball, my abdominals contract and my shoulders come off the ground. However, I do not actively contract my abdominals nor do I actively hold the contraction throughout the movement. I use my entire body to throw the ball, not just my chest and arms, and my arms direct the ball rather than supplying the power.

This is an example of an exercise used for core strength by many that is similar to a movement-related exercise used as a tool to teach rapid contraction and relaxation. The best athletes remain relaxed. When Usain Bolt runs, he does not consciously contract and relax his muscles. He does not actively contract his abdominal wall to maintain his posture. He has an amazing ability to contract and relax at the appropriate time and with the proper order of contractions.

When basketball trainers speak about the lack of core strength, they typically point out a flawed movement. They do not measure core strength or stability through a core exercise, like one measures upper body strength with a bench press test or lower body power with a vertical jump test.

The traditional test of core strength is the sit-up test, but this is flawed in several ways. First, a sit-up test tests more for strength endurance than strength or stability. Second, there is no specificity, and therefore no certainty of transfer, between an exercise that occurs lying down involving flexion and stability in a standing posture. Finally, Stuart McGill, the godfather of spine research, says that sit-ups place “devastating loads on the disks.” Other studies have suggested that a front squat activates the core musculature more than a sit-up. So, how does one measure core strength? How does one measure improvement? How much strength does one need?

The Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies recently published a critical review titled “The Myth of Core Stability” by Eyal Lederman [Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies (2010) 14, 84-98]. Lederman addresses the strength question:

To what force level do the trunk muscles need to co-contract in order to stabilize the spine? It seems that the answer is not very much.

During standing and walking the trunk muscles are minimally activated (Andersson et al., 1996). In standing the deep spinal erectors, psoas and quadratus lumborum are virtually silent! In some subjects there is no detectable EMG activity in these muscles.

As for strengthening the core muscles, he writes:

A recent study has demonstrated that as much as 70% MVC [maximal voluntary contraction] is needed to promote strength gains in abdominal muscle (Stevens et al., 2008). It is unlikely that during CS [core strength] exercise abdominal muscle would reach this force level (Stevens et al., 2007).

So, what should a trainer do when there is a noticeable skill deficiency attributed to lack of trunk stability? For instance, some ACL studies have identified lack of core strength as a precursor to ACL injuries, while others simply appear to lack total body coordination which impedes their ability to stop or even execute skilled movements like shooting or jump stops or to hold their proper defensive stance (posture).

Lederman reminds coaches and trainers to remember the specificity principle of motor learning. He cites a study that “assessed the effect of training on a Swiss ball on core stability muscles and the economy of running...The subjects got very good at using their muscles for sitting on a large inflatable rubber ball but it had no effect on their running performance.”

Lederman adds:

“Trunk control will change according to the specific activity the subject is practicing. Throwing a ball would require trunk control, which is different to running. Trunk control in running will be different in climbing and so on. There is no one universal exercise for trunk control that would account for the specific needs of all activities. Is it possible to train the trunk control to specific activity? Yes, and it is simple - just train in that activity and don’t worry about the trunk. The beauty of it all is that no matter what activity is carried out the trunk muscles are always specifically exercised.”

If one sees a trunk control problem while doing yoga poses, the athlete needs more practice doing the yoga poses. However, this does not mean that the athlete lacks trunk control when shooting a basketball or making a jump stop. Similarly, if the athlete struggles to execute a jump stop, yoga will not necessarily improve his trunk control on jump stops. Instead, practicing jump stops is more likely to lead to improved performance of jump stops and improved trunk control on jump stops.

As for attacking the core stability through the activity and asking an athlete to concentrate on his core, as many trainers do, would you ask an athlete to have such an internal focus of control when running or lifting weights or shooting a basketball?

Lederman answers:

Let’s imagine two scenarios where we are teaching a patient to lift a weight from the floor using a squat position. In the first scenario, we can give simple internal-focus advice such as bend your knees, and bring the weight close to your body, etc (van Dieen et al., 1999; Kingma et al., 2004). This type of instruction contains a mixture of external focusing (e.g. keep the object close to your body and between your knees) and internal focus about the body position during lifting. In the second scenario which is akin to CS training approach, the patient is given the following instructions: focus on co-contracting the hamstrings and the quads, gently release the gluteals, let the calf muscles elongate, while simultaneously shortening the tibialis anterior etc. Such complex internal focusing is the essence of CS training, but applied to the trunk muscles. It would be next to impossible for a person to learn simple tasks using such complicated internal-focus approach.

While core strength and core stability are buzzwords and make trainers and scouts sound knowledgable, what does it mean for sports performance? How does one measure the supposed lack of core strength? How does one train a player with poor trunk control? Do exercises on one’s back lead to improved trunk control in an upright position in a dynamic environment?

Stability is important to sports performance. However, stability is not just abdominal exercises. Stability is global: it includes the entire body working together, not a few muscles located around the spine. Isolating these abdominal muscles in training helps one attain a six-pack, but these exercises do not necessarily improve sports performance or trunk control in sports performance.

Instead, if you want to improve trunk control in a jump stop, start at the basics and progress. The basics of a jump stop would eliminate the ball and any pre-jump stop movement. Focus simply on the body stability when landing from a short jump. Next, add the ball, but no prior movement. Then, execute the stationary jump stop while catching the ball. Then, eliminate the ball and add movement before the jump stop. Next, move prior to the jump stop while holding the ball. Finally, return to the full jump stop with prior movement and ball manipulation (dribbling into the jump stop or receiving a pass). This is a simple progression of motor skill development from the simple to the complex, and provides the specificity required to develop trunk control for an activity.

Topics: Brian McCormick, Strength Training

Periodization for Sport: Part II by Brijesh Patel

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Sep 21, 2010 8:21:00 PM

Topics: Strength Training, Brijesh Patel

Periodization for Sport: Part I by Brijesh Patel

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Sep 21, 2010 8:20:00 PM

Topics: Strength Training, Brijesh Patel

Push Up Progression by Ray Eady

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Sep 21, 2010 8:18:00 PM

Topics: Ray Eady, Strength Training

Long Femurs? Gotta Single Leg Squat by Brijesh Patel

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Sep 21, 2010 8:12:00 PM

by Brijesh Patel

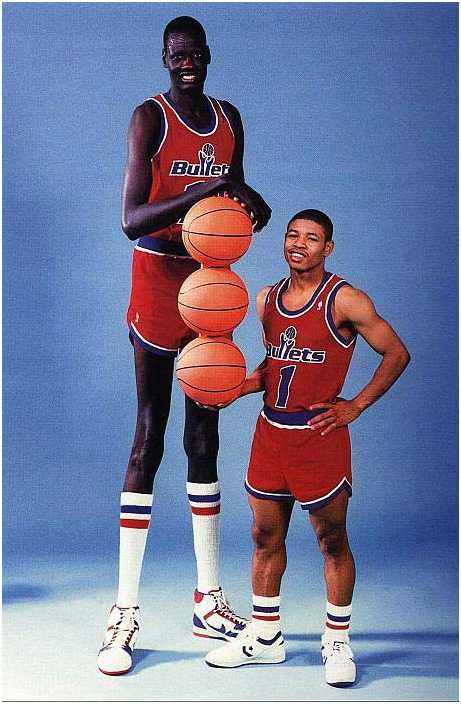

If you work with basketball athletes or taller athletes, you may have noticed that these athletes may struggle with not only double leg squatting but also single leg squatting. This is because their femurs tend to be longer than the average folk.

This comes back to simple physics as a longer lever is more difficult to control. And if an athlete has trouble controlling movements, injuries are sure to occur. Every joint within our body needs a certain amount of mobility (movement) and stability (control). If mobility is established then we need to add stability/control to it. In our case of long femurs and squatting, the first step is to make sure there is adequate mobility within the hip joint. If that is good we need to move onward to see why an athlete still has trouble performing the movement. The movements that tend to be the hardest to control are the eccentric actions of the squatting movement which are internal rotation and adduction. Now what muscles help control these femoral movements?

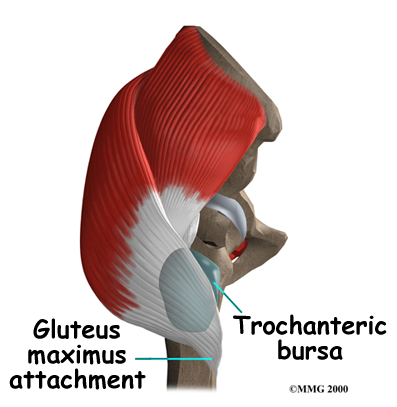

Namely the muscles that help to externally rotate and abduct the hip which are the gluteal muscles.

The Glute max, medius and minimus play a huge role in developing femoral control. And we have to train these muscles in ways that help to work on these actions.

If we don’t include exercises that help to work on femoral control than it could lead to knee issues in our athletes. Double leg squatting is a good starting point but having 2 fixed points of contact doesn’t challenge the hip musculature to the same degree as single leg work….and single leg unsupported to be specific.

Mike Boyle was the first strength coach that broke down single leg training into single leg supported and single leg unsupported. Single leg supported exercises is where you have 2 points of contact where one leg is performing the majority of the work. Examples are lunges, split squats, lateral squats, etc. Single leg unsupported work is where the body is supported on a single leg and the other leg is free (in the air). Examples of these exercises are single leg squats, single leg reaches, and pistol squats.

With basketball athletes and athletes with longer femurs it is imperative that single leg unsupported work be included to help develop the glutes to control the femur. Single leg squats to a box with a band above or below the knees is a great way to start and get the athlete to understand femoral control and the importance of it. You may need to start your taller athletes with a higher box and progressively move them down to a lower box as their strength and control improve.

We should all know the importance of single leg strength now, but if you are working with taller athletes make sure single leg unsupported work is included within your program.

What are other variations that you would include

Topics: Strength Training, Brijesh Patel

A Practical Approach To Torso Training Part II by Brijesh Patel

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Sep 21, 2010 8:09:00 PM

Topics: Strength Training, Brijesh Patel

A Practical Approach To Torso Training Part I by Brijesh Patel

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Sep 21, 2010 8:07:00 PM

Topics: Strength Training, Brijesh Patel

Time Efficient Training by Brijesh Patel

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Sep 21, 2010 8:04:00 PM

Topics: Strength Training, Brijesh Patel

Single Leg Squat Testing

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Sep 21, 2010 8:03:00 PM

By Devan McConnell

The problem with single leg training is that it's no fun. I've never come across an athlete who voluntarily wants to spend time performing unsupported single leg squats. Because of this fact, I recently engaged in a conversation with several of my colleagues about including pre-season tests which encourage our athletes to train the most important exercises over our summer programs.

By including a Single Leg Squat Test in the pre-season, most players will be sure to "remember" to hit this exercise while at home. If the players know there will be a specific test, they will train for it. However there was some debate over how to implement the test. Several ideas were thrown around, all having merit. A simple 10 or 20 rep test was one idea. Another variation was to perform "rounds" of 10 per leg. Percentage of BW was another variation. One coach talked of performing a 5RM test.

I think the trickiest part is figuring out exactly what we want out of Single Leg Squatting, and then figuring out exactly how to test for it. I tried a couple of different methods. First I had my females do a simple BW 20 or max rep test, where they basically just went for as many reps as possible on one leg, then the other. If they hit 20, I called the test. The average was 15. With my guys, I felt that this would not be challenging enough, and also I don't think a max rep test accurately looks at the quality I want trained with this exercise; functional strength. I'm not too concerned if my players have a great deal of muscular endurance with the single leg squat, I want them to be extremely strong on one leg.

The variation of the test I implemented with my men's team was a spin off of UMass Strength Coach Chris Boyko's idea of doing "rounds", combined with the idea of progressive resistance. I had my guys set up the box for parallel (between 14-16 inches depending on tibia height). The entire test was done with 5lbs dumbbells. I had them complete 5 reps at "bodyweight" on each leg, then put on a 10lbs vest. Then they did 5 more reps on each leg. If they completed that, they added another 10lbs vest, and continued in this manner until they came to failure. Failure would be falling off the box, fully sitting on the box, an extended rest between reps (subjective by me), or taking more than 20 seconds to add a vest and start the next round.

The high score was 7 vests on both legs, which 3 of my players were able to complete. That's a total of 35 reps per leg, and a finish of 70lbs. I'm not convinced this is exactly the test I want to use in the future, but it certainly gave an idea of several factors, including strength, muscular endurance, asymmetries, and compete level. The downside of course is the need to have multiple vests, length of time to do the test, lack of true "maximum strength", and inability to test more than a few guys at the same time.

Overall as an experiment it gave me a relatively good idea of the single leg strength of my guys, as well as a good indicator of their compete level. Also it gave my guys an idea of what "strong" is on one leg, and a goal to shoot for over the summer. However you view this variation, the important thing is that we continue to train our athletes to be strong on one leg and keep pushing the envelope to find out what that really means.

Topics: Strength Training, Devan McConnell