Articles & Resources

Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group

Recent Posts

Principles Of The Knee by Logan Schwartz

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Dec 6, 2010 7:34:00 PM

Topics: Guest Author, Health & Wellness

Periodization For The Next Generation by Shelby Turcotte

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Dec 6, 2010 7:20:00 PM

by Shelby Turcotte

“The one thing that is consistent with high school athletes is inconsistency.”

I can’t tell you the number of times that my perfectly constructed training programs have been derailed by kids missing workouts. Here is a short list of some of the reasons my athletes have missed sessions last minute or had to adjust an entire session: broken tibia at football practice; keys locked in car; stayed late for a test; mom had to drop off brother; practice went over; recruiting visit; I have to pick out my Halloween costume because there’s a dance tomorrow. Yes, a Halloween costume…I’m not kidding, needless to say I was less than impressed. There are literally thousands of reasons an athlete may not be able to complete your training program as prescribed.

It’s time to periodize for the next generation of athletes

I am aware of all of the research that supports undulating periodization and I do use it in certain instances. However, after seeing hundreds of athletes come through, I am more than convinced that the best form of periodization is less of a structured plan and more of a system with guidelines. In reality it is conjugate periodization-ish, but even with less science and more art. You see, the two biggest issues that I have with most periodization programs is that 1) They don’t adjust or adapt very well for missed session(s) or partial sessions; and 2) they don’t factor in for good days and bad days. You see, kids being kids, nothing about them or their life is all that predictable.

A typical day may consist of getting up at 6am after about 5-6 hours of restless sleep. Head to school where they will quickly finish their homework that is due during the next period (perhaps getting some “assistance” from the back section of their book, odd answers are still in there I believe). By the time 9am arrives they’ve realized they didn’t eat breakfast, so a bagel or cereal bar should do the trick. Their day continues in this fashion until they go to bed. Throw in a practice for a couple hours, some studying, homework, food, and possibly a shower (if they have time) before doing it all over again. If I’m lucky enough to see kids somewhere in that busy day, it may not be for long, and who knows what kind of a day they’re having—might be a great one, might be a tough one.

There is no way to have an exact plan for training an athlete or athletes in a situation like this. Don’t waste your time finding percentages based on max effort lifts; things change too frequently to know what a given kid will perform like in the weight room on any given day. I’m not saying that there isn’t a time and place for more structured periodization, but what I am saying is that for about 95% of the high school population they will be much better off with a loose set of guidelines which you will manipulate as the coach.

Next Generation Periodization Guidelines:

- Work in 3 week blocks. Forget 4 week blocks—and don’t structure a week for deloading. Why 3 weeks? Well, 4 weeks will often make kids bored, and 2 weeks isn’t enough time to get any growth and development. I’m not saying you can’t push a given movement for longer than 3 weeks, but you have to do it strategically.

- Don’t build in deload weeks. If someone needs a deload week you will know it. Typically the athletes will deload themselves. There are a few names they use for deloading: homework, vacation, games, and laziness. All are used and used often. You will know as a coach when you need to add in a deload week because kids start to look “messy.” If you’re a coach you know what I’m talking about.

- Follow the simple linear format of a volume phase followed by an intensification phase for your resistance training. Both should last in 6 week blocks (as stated above). Change the sets and reps according to your phases (volume or intensification). Don’t make it more complicated than it has to be. Get your athletes to put more weight on the bar and lift it more times.

- Push a given movement for 6 weeks at a time. After 6 weeks (2 3-week cycles), either switch the movement up or simply switch stance, grip, etc. The only exception to this is if you someone is really lacking in a given area and is still making progress. Other than that switch it up, kids get bored easily.

- If it’s important do it everyday. I got this one from Dan John’s book Never Let Go. I can’t make this point enough. We will do each of the following movements everyday in some capacity: vertical push, vertical pull, horizontal push, horizontal pull, knee dominant, hip dominant, total body explosive, anterior core, rotational (anti-rotational) core. There is something to be said for practicing a skill everyday—lifting and movements are no different.

- Always work different rep ranges. As stated above we will work all movements everyday in one way or another. This is also how I consider this structure a variation of conjugate periodization. An example of this would be warming up with a squatting variation for higher reps (12+), doing some reactive work for nervous system activation, and in the resistance portion of the workout working in the 5-8 rep range.

- Always do lower body movements first in the workout. Forget the science behind more motor units, hormone release, blah blah blah. You do lower body first because kids hate it and will always skip it if they have the opportunity. Put it this way: if you just finished a two hour basketball practice would you rather squat heavy or bench? This includes doing legs first…even on bench press Monday’s!

- Forget the whole “maintain” strength while in season. Move weight and get stronger. Sometimes I use the same terminology to explain that kids won’t make as much progress as the off-season, but let’s be honest—is there really an off-season anymore? Also, kids continually get stronger. If you push the weights in season you’ll be amazed at how strong they can get.

- Don’t change your rep schemes in season. Lift heavy. You don’t need tons of volume in season, especially on movements that kids will get in practices (i.e. if it’s basketball don’t program 20 minutes of plyo’s in the weight room.) They just got done doing 120 minutes of plyometric movements in practice…

- Kids recover amazingly fast. I am always astonished that you can push a kid hard in the weight room and the next day he’s in practice having the best practice of his life. That doesn’t mean bury a kid in the weight room, but it also doesn’t mean that you should plan to go “light.” If a kid isn’t recovering, you will know it (see above).

- Lift the day before games. I hear a bunch of bologna from parents and coaches alike about not lifting before games. Here’s the deal: you don’t tell your kids to not practice the day before a game because you are worried about their legs right? As long as the athletes have been in the weight room a couple of days a week they will be fine. It’s better to lift the day before a game than it is to miss a lift.

Shelby Turcotte (MS, PES, YCS) is southern Maine based high school strength & conditioning coach and the owner of Finer Points. For more information please visit his website: www.finer-points.com or visit his blog: www.shelbytrained.com.

Topics: Strength Training, Guest Author

What Is Wrong With Girls Basketball? by Brian McCormick

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Nov 28, 2010 3:41:00 PM

I picked up the following on another web site that covers primarily southern California prep players and teams. However, it closely mirrors many points made on this site previously (I deleted the player’s name and school):

As the negative stories started filtering out of the HAX tourney, perhaps the most significant was the oft-repeated observation that [D1] recruit K.S. has no desire. She’s a player with all the gifts to be a collegiate AA, yet, she plays as if she’d rather be anywhere other than the basketball court. If this were a reality show, a judge would have already put the question to her, “Do you really want to be here?” My belief is that she wants to come to [college] and if she has to play basketball in order to do it, so be it. During the tournament, numerous observers felt that she was content to let others do the dirty work and if the ball got in her hands, then the magic happened. Unfortunately, she was not the only player at the tournament who had that attitude.

Have we burned out these girls? Playing every day, every month of the year. Even though this is the first big high school tournament in the Southland [technically it is before the official start date of high school basketball practice], scores and scores of concerned fans were noticing that the girls were disinterested and unenthusiastic. Also, the girls were better athletes, but not better basketball players. Playing all those games hasn’t translated into higher skills because there’s no teaching or coaching. Watching player after player incorrectly perform a basic skill like a bounce pass or totally ignoring others like a close out, and you can only start wondering what these parents are paying the big bucks for. Oh, I know, it’s for the college scholie, and a lot of girls at the tournament have gotten that. Good for them. But have we lost a generation of players because of that single-minded goal? Watching some of the ghastly games that WBB put on during their first week, I’d say the prognosis is not encouraging.

Topics: Basketball Related, Brian McCormick

A Quick Note : Youth Training by Brian McCormick

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Nov 28, 2010 3:33:00 PM

by Brian McCormick

I generally refuse to train 8-year-olds. When parents call about a young player, I encourage the parents to invest in gymnastics or martial arts because of the benefits in terms of general strength and coordination as well as kinesthetic awareness.

The one 8-year-old who I agreed to train participated in a summer camp that I directed. Incidentally, teaching him how to shoot was easier than with any other player with whom I have worked. While he may not have developed many bad habits by that point, I attributed the ease of development to his weightlifting. At 8-years-old, he was working out with weights and doing cleans, snatches, squats and other lifts that conventional wisdom suggests are dangerous for children. At 8, he specialized in basketball. I encouraged him to play other sports because I am not a fan of early specialization. As he reached middle school, he played different sports and excelled in wrestling and football. Again, I attribute at least some of his success to his early weightlifting.

The New York Times ran an article this week featuring Dr. Avery Faigenbaum about the myths of youth weight lifting. The article highlighted research showing the safety of resistance training, despite the pervasive myths of stunting a child’s growth.

The article made two interesting points:

First, Dr. Faigenbaum said that children do not benefit in terms of hypertrophy like adults, but in terms of neurological changes. This makes sense, as the first adaptation that anyone makes when beginning a weight lifting program is neuromuscular. When you lift for the first time and see rapid gains immediately, those gains are not muscular strength; instead, it is the neuromuscular system firing more rapidly and efficiently which allows you to lift more weights.

When the eight-year-old did cleans, the improvements in terms of shooting were not due to muscular strength (at least initially). The resistance training did not make adaptations to shooting easier because he was stronger and therefore could shoot with better form from further distance. Instead, the ease was due to the neuromuscular improvements: he adapted to basketball-specific movements more quickly and easily. He understood the full-body coordination of a jump shot, while most 8-10-year-olds learn through segments and therefore do not exhibit the same full-body coordination.

Most players learn to shoot with a set shot. When they transition to a jump shot, the complexity is learning to coordinate the upper-body movement with the lower-body movement: the full-body coordination affects the transition as the body learns to turn these two movements into one (this is why I spend less and less time on form shooting drills). For the eight-year-old, he already had this movement pattern from the cleans, so his transition was easier.

The second interesting point was the lack of movement in today’s youth. Many people, including me, have written about the perils of overtraining in youth athletes. The important point is that the overtraining effects with young athletes are not necessarily due to the volume of the stress, but the lack of preparation for the physical stress.

“There was a time when children ‘weight trained’ by carrying milk pails and helping around the farm. Now few children, even young athletes, get sufficient activity’ to fully strengthen their muscles, tendons and other tissues. ‘If a kid sits in class or in front of a screen for hours and then you throw them out onto the soccer field or basketball court, they don’t have the tissue strength to withstand the forces involved in their sports. That can contribute to injury,’ said Lyle Micheli, M.D., the director of sports medicine at Children’s Hospital Boston and professor of orthopedic surgery at Harvard University.”

A coaching friend called me recently and told me that every U.S. Olympic Wrestling medalist in the last 30 years grew up on a farm. That makes sense, as children on a farm grow up in a more active environment and develop strength naturally through the farming. Consequently, their bodies are prepared for activities like wrestling.

The best way to prevent overtraining is not to limit the hours of activity, but to increase the opportunities for physical activity and to incorporate preparatory activities like resistance training even (or maybe especially) with young athletes.

Despite what most people think, weight lifting is highly unlikely to stunt a child’s growth or induce injury, unless the child lifts inappropriately. The benefits of weight lifting, however, are many.

Read the article here: http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/24/phys-ed-the-benefits-of-weight-training-for-kids/

Topics: Basketball Related, Brian McCormick

Are You Making The Right Decision by Eric Gahan

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Nov 28, 2010 3:33:00 PM

by Eric Gahan

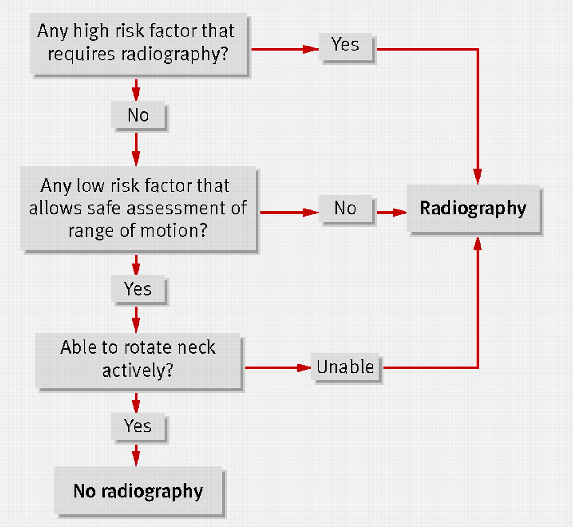

More and more as research develops and studies get published athletic trainers acquire tools to be more efficient and evidence based. One such tool established is the clinical prediction rule. Clinical prediction rules have been developed for many areas. One such area is the Canadian C-spine Rule (CCR) that has been published since 2003. With the publication of this clinical prediction rule we have evidenced based guidelines to send our patients for radiography of the cervical spine.

These guidelines give athletic trainers an evidenced based approach to sending an athlete for radiographs of the cervical spine.

The CCR first evaluates suitable patients for any of three high risk criteria:

• The first of the three is an age-factor, deeming any patient who is 65 years old to be at high risk.

• The second factor looks for any dangerous mechanism, including a fall from a height greater than 3 feet, a high-speed motor vehicle collision (greater than 100km/hr, with or without rollover or ejection), an accident involving a bike or motorized recreational vehicle, or a direct axial load that would place the patient at high risk for a C-spine injury.

• The third high-risk factor is paresthesias in any or all extremities. If any of the three high-risk factors applies to the patient, the CCR mandates radiography.

If the patient lacks any high-risk factor, the CCR then evaluates the patient for the presence of any low-risk factor that will eventually allow for safe assessment of cervical range of motion.

• The published low-risk factors are simple rear-end motor vehicle collisions, a patient found sitting in the Emergency Department or ambulatory after the accident, delayed onset of neck pain or absence of any midline cervical pain. If none of these low-risk factors applies to the patient, the CCR mandates radiography.

If, however, the patient has no high-risk factor and does have at least one low-risk factor, the CCR then assesses the patient’s ability to actively rotate their neck, both left and right, at a 45° angle, with or without pain.

• If the patient is physically unable to perform this exercise, radiography is indicated. If the patient can perform this manipulation, however, the CCR recommends that no radiography is necessary to rule-out significant cervical spine injury.

There are several situations where the CCR could be utilized in your practice as an athletic trainer:

• Athlete is under cut while coming down from a dunk. Athlete lands on the head, cervical, and thoracic area of the neck and upper back. While clearing head and neck and calming the injured athlete the CCR flow cart could easily be used in your clinical on-court evaluation.

• Athlete is diving for a loose ball and collides with another player. This is a situation that could pass the athlete on the first area of the flow chart, but when assessing for cervical mid-line pain and also active rotation is not possible, you send for radiographs.

Given this clinical prediction rule we have peer reviewed research to make decisions requiring radiographs of the cervical spine. This is an area where error cannot come into our clinical practice and can only make us better. Of course with every clinical prediction rule it is important to remember these are only tools to help give efficient and effective health care to our athletic population. As the profession of athletic training continues to gain respect in the health care community it is important remember some words of wisdom shared with me as an athletic training student at Canisius College, “Always practice as a clinician and not a technician.”

Reference:

1. Bandiera G, Stiell, IG, Wells GA et al. The Canadian C-Spine Rule performs

better than unstructured physician judgment. Annals of Emergency

Medicine 2003; 42, 395-402.

2. Hoffman JR, Wolfson AB, Todd K, Mower WR. Selective cervical spine

radiography in blunt trauma: methodology of the National Emergency XRadiography

Utilization Study (NEXUS). Annals of Emergency Medicine

1998; 32, 461-9.

3. Stiell IG, Wells GA,Vandeheem K, et al. The Canadian C-Spine rule study

for alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA 2001; 286: 1841-8.

4. Stiell IG, Clement CM, McKnight RD, et al. The Canadian C-Spine rule

versus the NEXUS low risk criteria in patients with trauma. New England

Journal of Medicine 2003; 349: 2510-8.

5. Hoffman JR, Schriger DL, Mower WR, et al. Low-risk criteria for cervical-

spine radiography in blunt trauma: a prospective study. Annals of

Emergency Medicine 1992; 21:1454-1460.

6. Dickinson G, Stiell IG, Schull M, et al. Retrospective application of the

NEXUS low-risk criteria for cervical-spine radiography in Canadian emergency

departments. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2004;43: 507-514.

7. Viccellio P, Simon H, Pressman BD, et al. A prospective multicenter study

of cervical spine injury in children. Pediatrics 2001;108: e20.

8. State of Maine Spinal Assessment Protocol. Maine EMS 2002.

9. Hoffman JR, Mower WR, Wolfson AB, et al. Validity of a set of clinical

criteria to rule out injury to the cervical spine in patients with blunt trauma.

New England Journal of Medicine 2000; 343: 94-99.

10. Heffernan, DS, Schermer, CR, Lu, SW. What defines a distracting injury

in cervical spine assessment. Journal of Trauma Injury, Infection, and

Critical Care 2005; 59: 1396-1399.

11. Ngo, B, Hoffman, JR, Mower, WR. Cervical spine injury in the very elderly.

American Society of Emergency Radiology 2000; 7:287-291.

12. Eyre, A. Overview and Comparison of NEXUS and Canadian Spine Rules. American Journal of Clinical Medicine 2006; 3: 12-15.

Topics: Health & Wellness, Eric Gahan

Hip Assessment by Logan Schwartz

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Nov 28, 2010 3:30:00 PM

Topics: Guest Author, Health & Wellness

I See The White Smoke by Fred Cantor

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Nov 21, 2010 6:24:00 PM

by Fred Cantor

Posted on NaturalStrength.com on June 20, 1999

There are too many "rules," too many "self-evident truths," and too much egotism and close-mindedness. The fact is, strength training is simple -- no, not the training itself, which needs to be brutally hard -- but the principles behind the training. Let the scientists and researchers argue amongst themselves -- the disagreements that they have now will be the same disagreements that they'll be having 5 and 10 years from now. I'm too busy training myself and others to wait for the white smoke to arise from the chimney and the "final word" on strength training to be released.

Because there will never be a final word.

Machines or free weight, Olympic lifting or non-Olympic lifting, periodization or high-intensity -- what's all the yelling about? Why is there so much anger -- on both sides-- if the other side disagrees? It's time that we stopped looking for differences in philosophies and started concentrating on the similarities -- because there are a lot more similarities than there are differences.

The goals on both sides are the same: We train to stay healthy, get stronger, and perform more effectively. All these goods can be met and have been met over the years, using machines or free weights, doing one set or multiple sets, and doing a variety of exercises. In fact, there are numerous variables in strength training -- sets, reps, equipment, exercises, etc. The factors, however, that are not debatable, the components that must be satisfied for a strength program to be successful are quite simple:

1. There must be intensity.

2. There must be overload.

3. There must be progression.

That's it. Nothing else. If you don't have those elements, no philosophy, no equipment, no methodology, and no supplement will make the program effective. The flip side, of course, is that if there is progression, overload, and intensity, every program will get good results. If you're not succeeding, look no further. Don't blame the equipment and don't blame the workout program: Remember, the same workout given to 10 people will get 10 different results. You must work hard -- every rep, every set, every day.

When designing a program, ask the following questions:

1. Is the program safe?

2. Is it effective?

3. Is it efficient?

4. Is it practical?

5. Is it purposeful?

6. Is it balanced?

If you cannot answer "yes" for an exercise or protocol, then exclude it from your workout. Make your decision objectively. Don't lose sight of what we're doing: strength training. You should never, ever be comfortable in a weight room. No one has ever reached their strength gain potential by being comfortable. If it's comfort you want, go some place else.

There are no secrets to success. Choose only productive exercises -- they should be chosen for functional, not cosmetic purposes. Do perfect repetitions with maximum effort -- you can either train hard and short or easy and long. Choose the former. Remember: As the intensity increases, the duration and frequency of the workouts decreases. Adjust your workout accordingly.

Above all, be aggressive. Don't fall in love with rep schemes or exercises, and be sure to make changes when adaptation occurs. Add weight. Add reps. Intensify sets. Don't be comfortable.

There are no gimmicks to successful strength training -- just hard, brutal work. Keep it simple and safe. Plan all workouts. Be accountable. Sleep and eat enough to enhance your progress. And finally, have fun and enjoy your workouts and appreciate the opportunity that you have to train hard and to challenge yourself.

That's something both sides can agree on.

Topics: Basketball Related, Guest Author

Priciples Of The Hip by Logan Schwartz

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Nov 21, 2010 3:00:00 PM

Topics: Guest Author, Health & Wellness

Pre-Season Training For Women's Basketball At The University Of Wisconsin: Part II by Ray Eady

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Nov 21, 2010 3:00:00 PM

Topics: Ray Eady, Strength Training

Preparing Your Athletes For Rotational Exercises Part II - Advanced Rotary Movements

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Nov 21, 2010 3:00:00 PM

by Art Horne

In the previous article entitled, Are You Qualified? Preparing Your Athletes For Rotational Exercises, I discussed the need to qualify your athletes for rotary movement prior to employing a long and extensive list of rotational core exercises including medicine ball throws and high level chopping patterns.

Below are a few advanced movements we employ after our athletes have demonstrated mastery in the rotary movements outlined previously. It should be noted that some athletes, especially the taller athletes, might not ever get to some of these movements and strength coaches and athletic trainers must resist the urge to progress these athletes along with the rest of the group until they have clearly shown mastery at the previous level. Remember, although the tall guys enjoy a clear advantage around the rim, performing simple plank holds and/or other strength movements just takes a little bit more effort – including even some of the most elementary rotary movements.

A Note on the Latissiumus Dorsi as a Lumbar Stabilizer

In a previous interview with Low Back Expert, Dr. Stu McGill, he mentions the importance of engaging the lats during exercises to help stiffen the core and provide a stable and strong base to work from. This point should be emphasized and facilitated when teaching the following exercises and also reinforced with those athletes having trouble “locking” their rib cage to their pelvis. To do so, simply stroke the lats from the shoulder down and into the thoracolumbar fascia to help facilitate this massive lumbar stabilizer. (Note: this is a great technique also when teaching athletes to pull from the floor/blocks and during squatting to help prevent shearing forces at the lumbar spine)

Stir The Pot with 12 o’clock Reach

"Stir the Pot" has become a staple in our program, but eventually our stronger guards master this movement and some additional challenge needs to be given to them to keep them both interested and adapting to increased stress. Once your athlete has mastered the basic exercise, which means a stable lumbar spine with no movement from rib cage to pelvis the following challenges can be made.

1. Reduce the width of their base of support by bringing their feet closer together.

2. Add an additional reach forward at the 12 o’clock position. Yes, this is actually an advanced “anti-extension” exercise, but a simple addition to a great exercise that gives you an additional bang for your buck.

3. Note: if your athlete is having trouble executing the beginner “stir the pot” instead of yelling at them over and over to hold their core tight, offer some simple tactile feedback by “raking” or “stroking” the lats on both sides to encourage this massive lumbar stabilizer to engage. This simple facilitation maneuver will give your athlete the needed cueing they lack to lock their spine in place.

Palloff Press with Lateral Walk

As I mentioned in the previous article this exercise progression should begin on the floor in a tall kneeling position and then eventually make its way up to standing. Because we have limited Keiser machines in our facility we rarely incorporate this particular advanced movement into our team programming but proves to be an excellent exercise when working in smaller groups or one on one.

Have the athlete press the resistance away from their sternum and hold this position. From there, incorporate a lateral walk without losing a stable torso.

- Remember: the lumbar spine was made to resist rotary motion, not to produce it.

Post – Pull and Press

This is a simple chop/lift variation that we include with our post players that challenges them to transfer outside forces through a stable spine. Because the position and action “smells like basketball” compliance and effort is always high with this exercise.

- Position your athlete on a 45 degree angle with their back towards the Keiser machine. In a deep post or athletic position first pull the cable stick across your body while maintaining a stable base and spine. This position should smell a lot like a deep post position in which your athlete must sit and take up space while asking for the ball with hands in front.

who ever said basketball isn’t a contact sport never played in the post

- Finish by pressing cable stick forward. Return and repeat.

- Emphasize transferring external load and resisting external rotational forces in a strong athletic position.

Front to Side Bridge

Although plank positions in and of themselves are not rotary movements, transitioning from one to the other certainly employs a great amount of rotary resistance. We start this exercise progression as I would image most coaches would, with simple plank holds. We then transition this simple exercise into a 5x5 second front-side planks. The athlete will hold the side plank position for 5 seconds and then transfer to the front plank – easy right? Actually, it’s not. The key here is to not allow the athlete to disassociate their hips/pelvis from their spine. Transitioning from the side to front plank is certainly the easier of the two but requires a ton of oblique involvement to keep the top shoulder and top hip moving in unison. From there, a static 5 second hold is performed from which the athlete transitions back. The final progression, as shown in the video, is a continuous front-side plank position without holds at either position. This is extremely challenging. Rarely will your tallest athletes be able to complete this task on the floor. Start these athletes by leaning to the wall to both learn and master this movement.

** Remember - help your athletes achieve success by facilitating their lats with a few simple strokes and/or offering a small bit of assistance at either the shoulder or hips until they learn how to lock their rib cage and pelvis together.

Modification for the taller athlete

Medicine Ball Rotational Throws

Besides the traditional medicine ball throws that you have seen and used in your own programming, two that can be used to emphasize locking the rib cage to the pelvis as well as establishing a solid base and post position are the Split Stance Side Toss (used mostly with the guards) and the Over Head Pivot throw (used mostly with the post players).

a)Split Stance Side Toss

- Hold the medicine ball on outside hip in a split stance position

- pivot on inside foot while quickly rotating outside hip (locked into the rib cage) and medicine ball around to face the wall

- toss the medicine ball at the wall as hips becomes parallel with wall. Emphasize “locking” the rib cage and pelvis together during the throw and establishing a strong finish position while catching the ball returning from the wall.

b)OH Pivot Series

- Hold medicine ball above head while standing perpendicular to wall.

- Pivot on inside foot while “locking” rib cage and pelvis together so that shoulders and hip move in unison.

** in both of the above medicine ball activities an athlete with poor technique will lead with the hips or shoulders and not “couple” them together. Both end positions should be strong and seated emphasizing a strong athletic post position.

** although almost all healthy athletes will be able to complete these exercises with terrible technique and without pain, an emphasis must be made as with all medicine ball activities to produce power through the hips and resist motion in the lumbar spine. By allowing the rib cage and pelvis to become grossly separated repeatedly will increase the chance of aberrant motion throughout the lumbar spine and thus subsequent pain and injury to follow. Post players that are not able to resist an external force (ie – Shaq, but then again who can right?) separating their upper and lower body during a fight for a deep post position or rebounding position will often find themselves at a huge disadvantage.

To quote Dr. Stu McGill, “Athletes utilizing explosive rotational exercises in search of world class performance will always end up chewing up their backs prior to reaching the point of world class performance in which they were in search of.”

Keiser with MB dynamic lift pattern

As shown in the previous article, the lift pattern can become a dynamic exercise and one that clearly replicates an athlete working his way to the rim from the low block. Since many schools do not have the use of a Keiser unit or enough units to make this exercise practical in a large group setting, we have incorporated the Verti-max units and have shown this exercise here using the Verti-max while holding a Core-ball for additional external resistance. The goal of the exercise again is to resist rotary forces about the lumbar spine while producing this motion through the hips and “locking” the rib cage and pelvis together.

Closing Thoughts:

As with all exercises, mastery takes time. Resist the urge to progress an athlete to the next level of difficulty prior to mastering the basics. This may even mean taking the taller athletes off the floor and starting them on a table or wall. If you are unsure whether your athlete is prepared for a rotary activity simply have them perform the prone shoulder touch again or continue to incorporate this activity into your daily warm-up to help groove this pattern.

Topics: Art Horne, Health & Wellness