Articles & Resources

Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group

Recent Posts

Got Training by Brijesh Patel

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Oct 24, 2010 11:50:00 AM

Topics: Strength Training, Brijesh Patel

The Renegade Row, by Jay DeMayo

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Oct 24, 2010 11:33:00 AM

Topics: Strength Training, Jay DeMayo

More Glutes Please - Part One by Art Horne

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Oct 23, 2010 10:53:00 AM

Are you hammering your athlete's glutes or just hammering your head against the wall?

Many athletic trainers and strength coaches will prescribe glute med work in their programs whether it be for rehabilitation, activation exercises before training or simply as part of an athlete's maintenance work - yet many of the problems for which we prescribe this work continues to show its ugly head during the basketball season.

Lets take a closer look at the work we are doing for the gluteus medius and what we might be missing in our athlete's program.

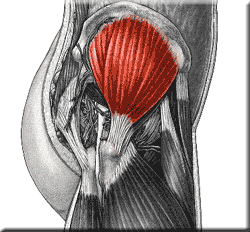

Origin: External surface of ilium between anterior and posterior gluteal lines.

Insertion: Lateral surface of the greater trochanter.

Innervation: Superior Gluteal Nerve (L4, L5, S1)

Function

All fibers abducts femur at the hip joint. Anterior fibers flex and medially rotate the hip. Posterior fibers extend and laterally rotate the hip. Most importantly, it holds the pelvis secure over the stance leg and prevents pelvic drop on the opposite swing side during walking.

Assessment

Palpation

With your patient/athlete side-lying, isolate the shape of the gluteus medius by placing the webbing of one hand along the iliac crest (from PSIS to nearly the ASIS) while the hand locates the greater trochanter. Your hands will form the pie-shaped outline of the gluteus medius. Palpate in this area from just below the iliac crest to the greater trochanter for the dense fibers of the gluteus medius. Ask your patient/athlete to abduct his/her hip slightly and you should feel the gluteus medius contract. (See attached diagrams.)

Hip Abduction Strength Test

• The patient is side lying with test leg on top.

• The therapist stands behind the patient and stabilizes with one hand at the hip, proximal to the greater trochanter.

• The other hand applies resistance across the lateral surface of the knee.

• Patient abducts hip against downward resistance

• If the patient is unable to perform the test side lying, place them in a supine position and feel for a gluteus medius contraction as they attempt to abduct their legs along the table.

• Note: During side lying hip abduction testing, Wilson (2005) points out that athletes “with weak hip abductors will attempt to compensate by recruiting their tensor fascia lata (flexing their hip), their external rotators (lateral pelvic rotation), or their quadratus lumborum (“hiking” their hip).”

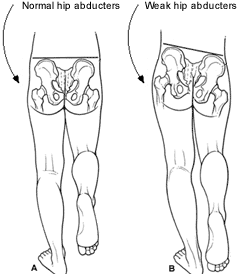

Trendelenburg’s Test for Gluteus Medius Weakness (Starkey, p293)

• Patient Position: Standing with weight evenly distributed between both feet.

• Lower patient’s shorts to the point that the iliac crests or PSIS is visible.

• Examiner Position: Standing, sitting, or kneeling behind patient.

• Procedure: The patient lifts the unaffected leg, standing on the affected leg.

• Positive Test: Pelvis lowers on the non-weight-bearing side.

• Implications: Insufficiency of the gluteus medius to support the torso in an erect position, indicating weakness in the muscle of decreased innervation.

Implications of Gluteus Medius (GM) dysfunction

Why we do what we do

Presswood et al (2008) state that “a weak or dysfunctional GM is linked to numerous injuries of the lower extremities and abnormalities in the gait cycle.” (p 41) The authors cite past research that implicates a weak/dysfunctional gluteus medius in Trendelenburg gait (see above), lower back pain, Iliotibial band syndrome, patellofemoral pain syndrome, ACL tears and other knee injuries, and ankle injuries. (p 42-43)

Trendelenburg Gait

During walking if a person’s GM, on either side, is weak the hip of the leg currently in the swing phase of walking will drop tilting the pelvis laterally. (See Trendelenburg Test above for more information) Presswood et al state that this will reduce gait efficiency and may lead to decreased running speed, and possibly lower back pain since that pelvis is not stabilized properly during activity. (p 42)

(Weak and inefficient Glute Med. on the basketball court = ENERGY LEAK during Cross Over Dribble. Want to move in the front plane more efficiently? Train the Frontal Plane.)

Lower Back Pain

Research published by Nelson-Wong et al (2007) showed that, “Muscle activation patterns at the hip may be a useful addition for screening individuals to identify those at risk for developing low back pain during standing.” (p 545) Twenty three subjects, 12 men and 11 women, were made to stand in a constrained position for 2 hours while their hip muscle activity was monitored. 65% of those studied developed low back pain during the test, and 76% of those subjects had reduced GM activation. Additionally, Nadler et al (2001) showed that hip muscle imbalance, specifically with GM weakness, was strongly associated with low back pain in female athletes.

Iliotibial (IT) Band Syndrome

Khaund and Flynn (2005) state that IT band syndrome “is caused by excessive friction of the distal iliotibial band as it slides over the lateral femoral epicondyle during repetitive flexion and extension of the knee resulting in friction and potential irritation.” (p 1545) Key clinical recommendations in this article are that hip abductor weakness can contribute to IT band syndrome, and that strength training emphasis needs to be placed on the gluteus medius. (p 1546) The authors go on to cite research by Fredericson et al (2000) that concluded that, “Long distance runners with ITBS have weaker hip abduction strength in the affected leg compared with their unaffected leg and unaffected long-distance runners. Additionally, symptom improvement with a successful return to the preinjury training program parallels improvement in hip abductor strength.” (p 169)

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS)

Presswood et al (2008) cite research that defines PFPS as “an overuse injury characterized by anterior knee pain, often aggravated with stairclimbing, squatting, or sitting for prolonged periods of time.” (p 42) The authors go on to state that “inhibition or dysfunction of the GM may contribute to decreased hip control, allowing greater femoral adduction and/or internal rotation. This produces a larger valgus vector at the knee, increasing the laterally directed forces acting on the patella and contributing to the patella tracking laterally.” (p 42)

Nakagawa et al (2008) set out to study the effect of strengthening PSPS diagnosed patients’ quadriceps along with the hip abductors and lateral rotators (intervention) vs. just strengthening the quadriceps (control). Only the patients who were in the group strengthening the hip abductors and rotators improved their perceived pain symptoms. The intervention group not only had a reduction in pain, they also had increased knee extension torque and GM EMG activity. The control group’s only change was an increase in knee torque.

ACL Injuries

Presswood et al (2008) states that excessive “knee valgus or rotation of the femur during landing is a potential mechanism for ACL injury.” (p 43) The authors go on to say that athletes with a high level of GM control and strength are better prepared to counter these movements. In addition, female athletes have a 6-8 times greater chance of ACL injury, possibly due to increased “knee valgus and/or hip rotation [relative to] male athletes.” (p 43)

Shimokochi et al (2008) searched for literature regarding noncontact ACL injuries between 1950 and 2007, to ascertain possible mechanisms of injury. After finding and analyzing 40 articles meeting their criteria, the authors’ main conclusion was that ACL “injuries often happen when an individual attempts to decelerate the body from a jump or forward running while the knee is in shallow flexion angle. At the time of injury, combined motions such as knee valgus and knee internal-external rotation are often noted.” (p 406) They also noted that the ACL is “loaded with anterior tibial shear forces. Unopposed quadriceps muscle forces produce anterior shear forces, possibly damaging the ACL, especially near full extension.” (p 406) These conclusions support the need for not only proper GM function to avoid ACL injuries, but also the need for proper hamstring strength and function to counteract overt quadriceps dominance, along with excessive knee valgus and rotation.

Ankle Injuries

Friel et al (2006) tested a group of 23 people, ages 18 to 52 years old, with a history of at least 2 ankle sprains to the same side with no injury to the other side, and no traumatic lower extremity injury with 3 months. The study found that the strength of the hip abductors on the previously injured side was significantly reduced compared to the uninvolved side. Based on past research the authors stated that “After lower limb ligamentous injuries, dynamic postural control of the lumbopelvic hip complex decreases.” (p 76) Coupled with past data and results of the current study, the authors concluded that if a person’s hip abductors are weak they will be unable to counteract normal lateral sway during gait, which can potentially lead to ankle injury.

Additionally, Beckman et al (1995) studied the reflex latency response of hip and ankle muscles during ankle inversion. The authors concluded that subjects with ankle hyper mobility had decreased latency (the gluteus medius fired prematurely) of hip activation after ankle inversion. The researchers hypothesized that this was a protective measure coordinated by the body’s motor neurons that compensate for the hyper mobile ankle, and they concluded that clinicians must address altered hip muscle recruitment patterns in patients with ankle sprains.

Suggestions for Improving Function and Strengthening the Gluteus Medius

Presswood et al, in the authors’ review of past gluteus medius literature, state that generally patients are “prescribed open-chain or single-leg stance exercises to initially strengthen the GM in a side-lying or weight-bearing position. Closed chain exercises are introduced during the later stages of rehabilitation, once basic strength has been developed.” (p 44-45)

In reference to sets, reps, and frequency, the authors go on to cite a position statement by the American Council of Sports Medicine states that “at least 2 training sessions a week that involve 2 to3 sets of between 6 to 15 repetitions per set will lead to considerable increases in muscular strength and endurance.” (p 50) However, every patient is different, so the authors go on to reference the book, Techniques in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation (McGraw-Hill Profession, 2001), and state that “for rehabilitation, strengthening exercises should be performed on a daily basis initially, with the number of repetitions and sets controlled by the patients’ level of pain, swelling, and response to exercise. As healing progresses, the muscle can be exercised every second day so the frequency becomes 3 to 4 times per week. Thus the exact loading parameters would appear to be dependent on the person’s injury and may vary between individuals.” (p 50)

With this in mind, the main goal of a GM strengthening program is to progressively overload the muscle so that it continues to develop muscular strength, control, and endurance. Review the article “Gluteus Medius: Applied Anatomy, Dysfunction, Assessment, and Progressive Strengthening” by Presswood et al as a starting place for more details.

Click here to view Common Gluteus Medius Strength Exercises.

Click below to view Uncommon Gluteus Medius Strength Exercises that you wish you were doing.

Summary

So what does this all mean and how does this apply to Basketball perforamance and health?

1. A strong and efficient GM is important in maintaining a healthy basketball athlete - Low back pain, knee pain and ankle problems (smells a lot like what keeps basketball athletes from playing the most doesn't it?) are all affected by GM dysfunction and weakness. Filling this gap in their training and maintenance program is the first step in keeping them on the floor.

2. Basketball = Knee Pain (or at least it used to). At one time basketball athletes were condemned to live out their careers with chronic knee pain because, "thats just part of the sport." With the work of Powers, Ireland and others, knee pain can be addressed by first attacking the hip (Charlie Weingroff presented on the importance of the Vertical Tibia and Knee Pain at this past year's Basketball Specific Conference ) and specifically addressing the GM. So turn off your ultrasound machines and get back to some good old fashion hip strengthening exercises.

3. Performance: a strong GM along with a trained and efficient Quadratus Lumborum/Obliques (lateral line) makes change of direction specifically in the frontal plane much more explosive and with less energy leakage enabling your athletes to move left to right at the speed of light.

Next week: Why all your glute med work still isn't working - The missing piece

Topics: Art Horne, Health & Wellness

20 Basic Training Tips For High School Basketball Players by Ray Eady

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Oct 23, 2010 10:38:00 AM

Why is it important for a basketball player to weight train? Simple, basketball is a physically demanding sport in which the player must be a complete athlete: strong and explosive while exhibiting fine motor skills when shooting, passing, rebounding, and dribbling. Basketball players must be conditioned to the demands of the sport. Weight training has been shown to increase the strength of muscular contractions, speed, and flexibility. The result is a stronger and faster player. Unfortunately, some players (high school and collegiate) do not understand the importance of strength training. In addition, those who do train seem to ignore the importance of lower body and core strength focusing entirely on upper body aesthetics. A basketball player must be able to efficiently run, shuffle, jump, and cut. All of these movements are performed primarily through the use of the ankles, knees, hips and core. In reality, players should possess the proper strength, power, flexibility, balance, coordination, and quickness to effectively compete on the court.

I’ve included 20 basic training tips for basketball players and coaches looking to get a competitive edge on their opponent.

1. Always start your weight room and on-court workouts with a general warm-up which is designed to raise your core temperature and increase blood flow to the muscles. Ten to fifteen minutes of jogging, form running, or active/dynamic flexibility drills are an excellent way to warm-up. Make sure your athletes take the warm-up drills seriously. Proper warm-up can reduce the chances of injuries.

2. Train the muscles of the core (hips, abdominals and low back). The core is the link between the upper and lower extremities. Without a strong core, athletic performance is limited. Forces generated from the legs and hips can be transferred into efficient movements when the core is solid and strong. This translates into running faster and jumping higher.

3. Train the core in a sports specific manner (on your feet). Medicine ball drills (i.e. chest pass throws, side throws, overhead throws, etc.) are an excellent way to strengthen the core and develop total body power.

4. The majority of training should include exercises that are closed-chain (standing on your feet), multi-joint (i.e. squats, squat jumps, lunges) and multi-planar (i.e. lateral lunges, 45° lunges, lateral step-ups).

5. Do exercises that focus on single leg strength and power. Players typically run and jump off one (1) leg to make lay-ups, make sharp running cuts, and to play defense (i.e. defensive slides).

6. Strengthen the muscles of the posterior and lateral hip (i.e. hamstrings and glutes). These muscles play an important role in rebounding, boxing out, blocking shots, and taking jump shots.

7. Train movements not muscles. The kinetic chain which consists of the nervous system, the muscular system, and the articular system (joints) must work interdependently to provide efficient movement. Strength training goals should focus on improving athleticism and movement on the court.

8. Drills to improve reaction time, footspeed, and eye-hand-feet coordination (i.e. stealing a ball from an opponent) should be included in your workouts.

9. Common injuries in basketball occur at the ankles and knees. Lower body exercises are crucial in reducing injuries in the lower extremities. Remember, athletes train to reduce the chances of injuries associated with their sport.

10. Use a variety of equipment for training (i.e. bodyweight, weighted vest, medicine balls, bands, manual resistance, dumbbells, barbells, slideboards, agility ladders, etc.). They all provide a training stimulus for improving on-court performance.

11. Incorporate exercises to improve the strength and the range of motion at the ankles. Most players tend to play with their ankles taped or with ankle braces which can lead to a lack of mobility.

12. Players should learn how to land and distribute ground forces from joints to muscle. Learning how to land on one (1) leg in multiple directions should be included in a training session once the athlete has mastered landing on two (2) feet.

13. Perform a static stretch routine after each workout session to:

1. Increase flexibility

2. Delay and lessen the on-set of muscle soreness.

14. Drink a post-workout shake consisting of protein and carbohydrates after each training session to re-fuel the body.

15. Drink plenty of water and remain hydrated. A lost of 2% of bodyweight due to dehydration can cause a 10-20% decrease in athletic performance.

16. Eat a minimum of three (3) meals per day consisting of protein, (good) carbohydrates and low fat for energy and to maintain or increase lean muscle tissue. However, it is recommended that athletes have at least six (6) meals a day.

17. Absolute speed (or linear speed) is not necessarily important in basketball. Lateral speed and the ability to accelerate, decelerate, and change direction is crucial. Cone drills, slideboards, and agility ladders are excellent for developing lateral quickness and agility.

18. Research has proven that basketball is predominately an ANAEROBIC/FAST GLYCOLYSIS sport (non-endurance). Basically, it’s a game of brief but intense and repeated burst of action and the ability to recover quickly is vital for playing hard. Therefore, conditioning must mimic the energy demands of the sport. Sprinting drills, interval runs and shuttle runs should constitute the majority of training. Aerobic training or long distance running will have a negative impact on developing speed, strength and power.

19. Learn how to think and play under fatigue. Circuit training with a work to rest ratio of 1:1 or 2:1 is a good training method at accomplishing this task.

20. Proper rest is needed to recover from strenuous workouts. Athletes should aim to get at least seven (7) hours of sleep at night.

Topics: Ray Eady, Basketball Related

How Do You Measure The Success Of A Strength And Conditioning Program? A Question by Ray Eady

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Oct 16, 2010 8:21:00 PM

Is it measured in wins, loses, injury rates, athlete's experience, compliance and satisfaction by the coaching staff, etc.? In the NBA, strength and conditioning coaches are measured on the basis of games missed due to injury. Therefore, if players are not missing games due to injury but the respective team finishes the season with a losing record is this still considered successful?

Thoughts?

Ray Eady, University of Wisconsin

Good question. This is a problem seen for many years and will continue for many years in our profession.

I feel that some of the measurement is due to the administration, organization, coaches and how they view it.

Obviously, wins and losses are a big key to how people in charge will respond. Keeping players on the court, field playing and developing well in the areas necessary for success is a huge part of the job. Pressure placed on coaches by upper level management for not enough wins eventually will trickle down to the strength program. This is regardless of any success with a lack of injuries, athletes experience, compliance, and coaching staff’s happiness.

I hope this answers it somewhat; it is a very open question.

RON – Purdue

_________________________________________________

How do I measure success by keeping our guys healthy and how many games did players miss - that is a quantitative approach. I also see success from a qualitative standpoint in what kind of impact does our program have on them from a mental stand point:

I.e. Are we making athletes more confident b/c of their improved strength, body comp, conditioning, power, etc.

Are we making athletes better by improving their mental state and teaching them how to remain positive and not show defeat and frustration during difficult tasks?

Are we making athletes better by asking them to themselves and their teammates accountable?

Are we making athletes better because they start to care more about their bodies inside and outside the weight room (attentive to nutrition, recovery, extra workouts, etc.)?

These are all things that make my program successful - as well as the feedback that I get from the athletes about what we are doing - if I see them buy into what we are doing, then I know I'm being successful.

How do sport coaches measure success - they see performance numbers increase, they see that they are healthy, they see improvement on the field/court/ice, etc.

I don't think we have a direct result in wins/losses but we do have an indirect effect:

1. are the athletes able to with stand the rigors of the sport (conditioning, strength, power, etc) 2. are the athletes resilient enough to bounce back from difficult practices (mobility, flexibility, stability, recovery) 3. are the athletes confident in their preparation that they won't crumble under the pressure of competition

Unfortunately if teams lose but stay healthy there might be a trickle down effect to the strength coach, b/c everybody is quick to point the finger during difficult times but in reality we don't have any technical or tactical effect upon the game itself - our job is done prior to the ball being tipped.

Brijesh Patel

______________________________________________________

How do I measure success? Injury rates and performance indicators such as vertical, 10 yard, 4 jump, etc.

How do sport coaches measure success? I think that depends. Some only care about wins/losses. Some just care about bench/squat/clean numbers. If we are lucky, they understand our field a little more "globally" and realize the best thing we can do for our athletes is improve their chances of staying on the court/field.

Devan – Stanford

______________________________________________________

Devan,

If performance indicators improve and injury rates decrease but the team still performs poorly in the win/lose column is that still considered successful?

Granted, as strength coaches, we can't control many variables: recruiting, game strategy, etc. etc. but should we still take some accountability for wins and loses?

Ray – Wisconsin

______________________________________________________

I don't think I can say it better than B did.

If performance indicators increase and injuries decrease, I believe we have done our job. As B stated, their may be trickle down if we lose, but we really don't have direct influence over those stats, so while I do take it personally, in the end we can't claim victories nor SHOULD we be held over the fire for losses. Not real world obviously.

I will add 2 aspects to my evaluation of a successful program:

1. FMS scores improve. I am a big believer in this screen, and though it could be seen as the same as injury rates decreasing, I do get fired up for my athletes when they improve their scores.

2. As B alluded too, how much have our athletes changed for the positive and grown as people when they leave. At then end of the day, very few of them will make money playing their sport, and even if they do, if they leave a more responsible, confident, "better" human being than when they arrived, and my program had anything to do with that, I view my time with them as successful.

D – Stanford

______________________________________________________

When a high school athlete signs their letter of intent, their #1 goal is to play [and play immediately and long-term]. Simple! They choose that "specific" collegiate program because that program gives them the BEST opportunity to achieve that goal. Therefore, success [for me] is helping that player [who signs that letter of intent] achieve the physical and mental tools needed to compete in the sport they LOVE. Basically, creating a POSITIVE experience and environment for the athlete when they are in a strength training [conditioning] session and using that environment as a catalyst for on field, court, or ice success.

Of course, in order to achieve that positive experience and/or environment we must keep our players healthy [first and foremost]. Nothing is more discouraging for a player than not being able to play [THE SPORT THEY LOVE] because of an injury. Positive experience/environment also means helping that athlete achieve the physical attributes that are needed to excel in the sport and giving them the motivation and confidence needed to be successful on AND OFF the playing field. In a nutshell, that is all I can control.

I agree, I don't think we have a direct result in wins/loses; however, our yearly interaction with the players can definitely influence how they compete. We can all agree, outside of the coaching staff, we spend the most time with the players than any other person within the athletic department. Therefore, if our interactions [and environment] with the players are not positive, I believe it can have some influence on wins/loses.

In the end, the best testimonial must come from the athletes. Athletes with positive experiences that are achieving positive results is a key indicator of success.

Ray – Wisconsin

______________________________________________________

I’ve always looked at success from both a strength program and a sports medicine perspective as simply related to the number of shots being put up each year. This is clearly related to the total games missed due to injury – but it goes one step further. Not being able to play in a game due to injury is devastating for both coaching staff and athlete, but not being able to practice for the days leading up to games week after week also has a tremendous effect on “success” both from a team perspective (wins/losses) but also overall skill development. Not being able to practice day in and day out limits reps on the press-break, in-bounds plays and “getting up shots” not to mention the opportunity to develop strength in the weight room. At the end of the day, the ability to endure the rigors of college basketball day in and day out is a huge factor when addressing this question.

The second part is simply about filling the gaps. This is twofold: First, it starts with assessment and addressing the needs and deficiencies of the athlete prior to injury. I think we all get that. The second part is about filling the gaps associated specifically to the success of the basketball athlete. Mike Curtis’ video that just recently came out I think summarizes what I am about to say. Our job is to create better basketball players – not better “weight room athletes”. Strength development is certainly a large piece of this, but should not be the end goal. Creating athletes who are strong and explosive in the frontal plane (especially for guards) is paramount in my eyes and simply cannot be done with traditional strength training (squat, bench and clean). Guards live and die by the cross-over, either putting on their opponent or defending it. If your program is not addressing this unique, yet trainable quality, I’d say you’re not filling the right gaps.

Art – Northeastern University

Topics: Ray Eady, Basketball Related

Carrying Your Core by Jay DeMayo

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Oct 14, 2010 9:17:00 PM

To view this article click HERE.

Topics: Strength Training, Jay DeMayo

Jump Training For Basketball by StrongerTeamdotcom

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Oct 14, 2010 9:09:00 PM

Topics: Guest Author, Vertical Jump Training

University of Virginia Men's Basketball Summer Training

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Oct 14, 2010 8:55:00 PM

Topics: Basketball Related, Mike Curtis

Brian McCormick To Kenya - Basketball Breaking Down Borders

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Oct 14, 2010 8:36:00 PM

Since I published Cross Over: The New Model of Youth Basketball Development in 2006, many coaches have contacted me. One of the first was Harrison Kaudia from ALSA Basketball in Kenya. Around 2007, I sent Harrison some copies of Cross Over for him to use with his aspiring coaches and players, and we have communicated ever since. Later, I heard from Isaac Kwapong of Dynasty Basketball in Accra, Ghana. Isaac uses the online strength training program that I created at www.trainforhoops.com with all of his players, and he uses the curriculum from my Playmakers Basketball Development League during his summer camp.

Recently, I put them in touch via email and joined Dynasty's Advisory Board. My plan was to save money to visit the two programs next summer, as both run summer camps and would like me to assist. Also, Harrison asked me about the feasibility of me drafting a curriculum for basketball course for an informal setting in communities and a formal setting in a college. Without having been there, it is difficult to write a curriculum, so a visit to see his programs would enable me to complete such a program for him.

Recently, I saw a contest through British Airways to win a free flight anywhere that BA flies, and I entered. If I win, the ticket will cover my fare to Kenya and I'll find a way from there to Ghana. Isaac and Harrison are passionate and enthusiastic about basketball and helping children and young adults, and I want to offer them whatever help that I can. While I continue to support via email and e-books, a visit to work with coaches and players will enable me to help them in a far more personal way, and they, in turn, will help hundreds or thousands in their communities.

To help me get to Kenya, follow this link and vote.

A Question Of Conditioning: A Look Back At How It All Started - One Year Ago

Posted by Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group on Oct 9, 2010 7:02:00 PM

by Art Horne

About one year ago, a question on conditioning came up among a small community of strength coaches and friends. From this the idea of EVERYTHING BASKETBALL was born. Today, EVERYTHING BASKETBALL continues to highlight the very best basketball professionals from across North America from all professional backgrounds and affiliations.

Thanks for continuing to share your ideas, videos and training advice.

The first question

______________________________________________________

Coaches,

I'm starting to put together my pre-season conditioning program for hoops and wanted to know if any of you have ever done the sideline ladder drill and if so, twice?

For example - one time up and down the ladder is this:

2,4,8,12,16,12,8,4,2

I want to put a progression together where we go up and down the ladder twice. Didn't know if this is too much or even reasonable.

Please let me know what you all think (even if I'm crazy to think this) and what your experience is with this.

If you could reply to all that would be great - that way we could all learn from this.

Thanks and I hope everybody is having a great summer,

B

--

Brijesh Patel

Head Strength and Conditioning Coach

Quinnipiac University

_______________________________________________________

B,

I will try to be brief and elaborate later if you would like. I am out of town and typing on a blackberry. I have used ladders in the past and they have predominantly been of the full-court variety for many of the reasons Shawn pointed out with change of direction.

The last couple of years I've been utilizing the heart rate monitors during our energy system development like Ray and have been doing a tempo/ladder type drills during the pre-season. I have always been more concerned about the total volume and how to manipulate it in conjunction with pick-up games.

I attempt to mimic the variety of distances and duration of efforts we incur in competition while still managing volume I have done sets of 3-5 repetitions for 4-6 total sets of varying distances. We know the court is roughly 30 meters. We can do runs of 30m(1), 60m(2), 105m(3.5), 150m(5), and 210m(7) at different gears (% of effort)in a set in any sequence or combination with varying amounts of active rest (1:1, 1:2, etc)between reps. Between sets is active recovery usually 120sec, about the amount of time for a TV timeout or foul called and free throws. I have found that the HR data and reports after show we have taxed both systems and the graphs look like those of game play. Doing it this way I can track the accumulated volume and adjust based on much playing and individuals they are doing and the HR data can give me signs of overreaching if we are doing too much.

I can go over the progression and other components of some the ESD with you next week if you want to call.

Mike

Mike Curtis, M.Ed., CSCS, USAW, SCCC, NASM-PES, CES Head Strength & Conditioning Coach, Men's Basketball University of Virginia Athletics

__________________________________________________________________________

Brijesh – Ray Eady (Wisconsin) and I were talking last night and he thought that maybe the women needed more change of direction so that they learn how to move more appropriately and transfer force, etc better... more turns means more reps/opportunities for learning? Or more opportunity to get hurt?

What do you think?

Art Horne

Northeastern University

_______________________________________________________

Art

That's a great point and I was thinking of that too - I like them performing more change of directions to make them more "athletic" but also worry about all the eccentric contractions.

I think I'm going to stick with the sideline but go with Ray and take out the "12" so we'll go:

2, 4, 8, 16

And work up to doing 3-4 sets of that....I may not go down the ladder but just go up like Ray does.

What do you do for pre-season condo?

Brijesh Patel

_______________________________________________________

Brijesh:

Ill have to send you the stuff, but basically we do five days.

- We perform your metabolic conditioning sequence to end each week prior to the beginning of practice so I think we are on week 6 now?

- slide board/bike combos (because we don't have enough of either so we split then switch) slide board 30:30, bike 20:40 on:off

- speed/metabolic with tire runs, sleds and prowlers

- lastly a plate circuit that has a tremendous effect which starts at 20:40, 30:30, and ends with 40:20

- On Sundays we do a pool day which is mostly movement based and acts as a recovery but we finish with some conditioning then too.

Art

_______________________________________________________

As they say the rest is history……..

Best of luck this basketball season.

Topics: Art Horne, Conditioning-Agility-Speed