by Art Horne

In the previous article entitled, Are You Qualified? Preparing Your Athletes For Rotational Exercises, I discussed the need to qualify your athletes for rotary movement prior to employing a long and extensive list of rotational core exercises including medicine ball throws and high level chopping patterns.

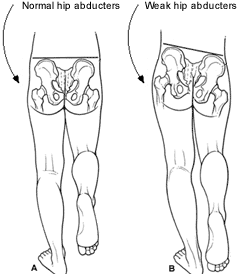

Below are a few advanced movements we employ after our athletes have demonstrated mastery in the rotary movements outlined previously. It should be noted that some athletes, especially the taller athletes, might not ever get to some of these movements and strength coaches and athletic trainers must resist the urge to progress these athletes along with the rest of the group until they have clearly shown mastery at the previous level. Remember, although the tall guys enjoy a clear advantage around the rim, performing simple plank holds and/or other strength movements just takes a little bit more effort – including even some of the most elementary rotary movements.

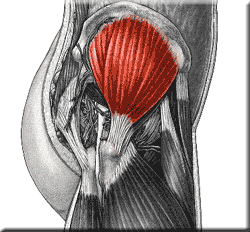

A Note on the Latissiumus Dorsi as a Lumbar Stabilizer

In a previous interview with Low Back Expert, Dr. Stu McGill, he mentions the importance of engaging the lats during exercises to help stiffen the core and provide a stable and strong base to work from. This point should be emphasized and facilitated when teaching the following exercises and also reinforced with those athletes having trouble “locking” their rib cage to their pelvis. To do so, simply stroke the lats from the shoulder down and into the thoracolumbar fascia to help facilitate this massive lumbar stabilizer. (Note: this is a great technique also when teaching athletes to pull from the floor/blocks and during squatting to help prevent shearing forces at the lumbar spine)

Stir The Pot with 12 o’clock Reach

"Stir the Pot" has become a staple in our program, but eventually our stronger guards master this movement and some additional challenge needs to be given to them to keep them both interested and adapting to increased stress. Once your athlete has mastered the basic exercise, which means a stable lumbar spine with no movement from rib cage to pelvis the following challenges can be made.

1. Reduce the width of their base of support by bringing their feet closer together.

2. Add an additional reach forward at the 12 o’clock position. Yes, this is actually an advanced “anti-extension” exercise, but a simple addition to a great exercise that gives you an additional bang for your buck.

3. Note: if your athlete is having trouble executing the beginner “stir the pot” instead of yelling at them over and over to hold their core tight, offer some simple tactile feedback by “raking” or “stroking” the lats on both sides to encourage this massive lumbar stabilizer to engage. This simple facilitation maneuver will give your athlete the needed cueing they lack to lock their spine in place.

Palloff Press with Lateral Walk

As I mentioned in the previous article this exercise progression should begin on the floor in a tall kneeling position and then eventually make its way up to standing. Because we have limited Keiser machines in our facility we rarely incorporate this particular advanced movement into our team programming but proves to be an excellent exercise when working in smaller groups or one on one.

Have the athlete press the resistance away from their sternum and hold this position. From there, incorporate a lateral walk without losing a stable torso.

- Remember: the lumbar spine was made to resist rotary motion, not to produce it.

Post – Pull and Press

This is a simple chop/lift variation that we include with our post players that challenges them to transfer outside forces through a stable spine. Because the position and action “smells like basketball” compliance and effort is always high with this exercise.

- Position your athlete on a 45 degree angle with their back towards the Keiser machine. In a deep post or athletic position first pull the cable stick across your body while maintaining a stable base and spine. This position should smell a lot like a deep post position in which your athlete must sit and take up space while asking for the ball with hands in front.

who ever said basketball isn’t a contact sport never played in the post

- Finish by pressing cable stick forward. Return and repeat.

- Emphasize transferring external load and resisting external rotational forces in a strong athletic position.

Front to Side Bridge

Although plank positions in and of themselves are not rotary movements, transitioning from one to the other certainly employs a great amount of rotary resistance. We start this exercise progression as I would image most coaches would, with simple plank holds. We then transition this simple exercise into a 5x5 second front-side planks. The athlete will hold the side plank position for 5 seconds and then transfer to the front plank – easy right? Actually, it’s not. The key here is to not allow the athlete to disassociate their hips/pelvis from their spine. Transitioning from the side to front plank is certainly the easier of the two but requires a ton of oblique involvement to keep the top shoulder and top hip moving in unison. From there, a static 5 second hold is performed from which the athlete transitions back. The final progression, as shown in the video, is a continuous front-side plank position without holds at either position. This is extremely challenging. Rarely will your tallest athletes be able to complete this task on the floor. Start these athletes by leaning to the wall to both learn and master this movement.

** Remember - help your athletes achieve success by facilitating their lats with a few simple strokes and/or offering a small bit of assistance at either the shoulder or hips until they learn how to lock their rib cage and pelvis together.

Modification for the taller athlete

Medicine Ball Rotational Throws

Besides the traditional medicine ball throws that you have seen and used in your own programming, two that can be used to emphasize locking the rib cage to the pelvis as well as establishing a solid base and post position are the Split Stance Side Toss (used mostly with the guards) and the Over Head Pivot throw (used mostly with the post players).

a)Split Stance Side Toss

- Hold the medicine ball on outside hip in a split stance position

- pivot on inside foot while quickly rotating outside hip (locked into the rib cage) and medicine ball around to face the wall

- toss the medicine ball at the wall as hips becomes parallel with wall. Emphasize “locking” the rib cage and pelvis together during the throw and establishing a strong finish position while catching the ball returning from the wall.

b)OH Pivot Series

- Hold medicine ball above head while standing perpendicular to wall.

- Pivot on inside foot while “locking” rib cage and pelvis together so that shoulders and hip move in unison.

** in both of the above medicine ball activities an athlete with poor technique will lead with the hips or shoulders and not “couple” them together. Both end positions should be strong and seated emphasizing a strong athletic post position.

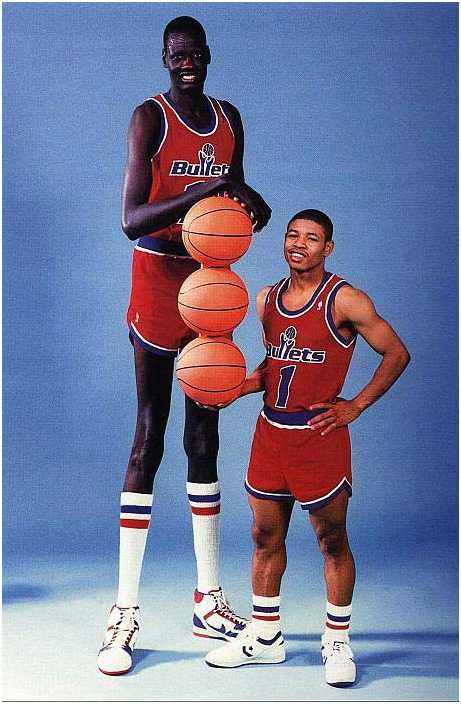

** although almost all healthy athletes will be able to complete these exercises with terrible technique and without pain, an emphasis must be made as with all medicine ball activities to produce power through the hips and resist motion in the lumbar spine. By allowing the rib cage and pelvis to become grossly separated repeatedly will increase the chance of aberrant motion throughout the lumbar spine and thus subsequent pain and injury to follow. Post players that are not able to resist an external force (ie – Shaq, but then again who can right?) separating their upper and lower body during a fight for a deep post position or rebounding position will often find themselves at a huge disadvantage.

To quote Dr. Stu McGill, “Athletes utilizing explosive rotational exercises in search of world class performance will always end up chewing up their backs prior to reaching the point of world class performance in which they were in search of.”

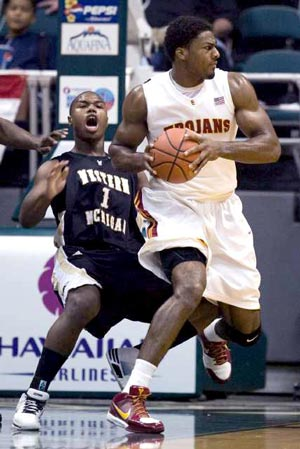

Keiser with MB dynamic lift pattern

As shown in the previous article, the lift pattern can become a dynamic exercise and one that clearly replicates an athlete working his way to the rim from the low block. Since many schools do not have the use of a Keiser unit or enough units to make this exercise practical in a large group setting, we have incorporated the Verti-max units and have shown this exercise here using the Verti-max while holding a Core-ball for additional external resistance. The goal of the exercise again is to resist rotary forces about the lumbar spine while producing this motion through the hips and “locking” the rib cage and pelvis together.

Closing Thoughts:

As with all exercises, mastery takes time. Resist the urge to progress an athlete to the next level of difficulty prior to mastering the basics. This may even mean taking the taller athletes off the floor and starting them on a table or wall. If you are unsure whether your athlete is prepared for a rotary activity simply have them perform the prone shoulder touch again or continue to incorporate this activity into your daily warm-up to help groove this pattern.