By Art Horne

It’s easy to get athletes and patients 80% -90% better after injury or surgery. It’s the last 10-20% that sets great rehabilitation specialists apart from their peers.

One of the most overlooked and underappreciated exercises regardless of the type of injury rehabilitation program you’re working with is the Hip Hinge. Teaching it, Grooving it, and then Challenging it under load is rarely seen in most athletic training rooms and physical therapy centers, yet it’s importance in the overall success of your rehab program is paramount. Whether you’re dealing with a low back pain patient or any myriad of lower extremity pathologies, a properly executed hip hinge pattern will ensure not only a smooth transition from rehab to performance but also appropriately challenges your patients during their rehabilitation program with a safe and progressive Ground Based-Function Based exercise.

Take the low back pain patient for example. As Stuart McGill makes mention to, most LBP patients utilize their backs entirely too much during simple everyday tasks such as tying their shoes, picking up objects from the floor and sitting and rising from chairs. By teaching and enabling your patients to accomplish these tasks through a safely executed hip hinge pattern, you’ll affectively be sparing their backs during ADL’s and alleviating perhaps hundreds of subsequent flexion moments throughout the day. By putting these stresses into the hips instead of the low back will enable your patients the opportunity to actually perform strengthening exercises with you during their office/athletic training room visit instead of constantly dealing with pain caused by faulty movement patterns.

No amount of moist heat packs and massage can make up for poor daily back hygiene.

In the case of the anterior knee pain patient, hip hinging allows them an opportunity to load their posterior chain including the glutes and hamstrings (both often neglected since you can’t see them while looking in the mirror) while avoiding loading an already overloaded quadriceps group. Stronger posterior chain muscles equates to less knee pain, not to mention a considerable performance enhancement boost when it comes to jumping and sprinting.

When it comes right down to it, all athletes and patients should be able to separate their hips from their back in both a 2-legged and single leg stance. Whether its knee, hip or other LE injury pain, athletic trainers, physical therapists or performance coaches should be able to look at this movement pattern and address any concerns IN ADDITION to their traditional rehab program. Now it’s up to you to teach them!

How do I start?

The Hip hinge pattern can be easily taught, standardized and grooved with a stick series.

Teaching the Stick Series:

1. Take any stick, PVC pipe, wood dowel, or broom stick and place along their spine. Be sure to keep the stick in contact with three points (head, back and butt crack) throughout entire movement.

2. Reach butt backwards; knees should have slight bend.

3. Start with two feet on ground, progress to single leg stance.

4. This is not a squat pattern! Movement should be through the hips – not a knee dominant movement

5. Maintain a packed neck throughout the series(c-spine in-line with sternum throughout movement). ** This position should also be taught and maintained during over exercises such as the Bird-Dog, but that’s for another post.

6. Be sure to maintain strict form and three points of contact at all times.

7. **While the stick is on the back of the athlete/patient, we continue with a lunge pattern (as shown in the video) which helps solidify their spine position and teaches them to drive through their front foot but is not necessary if you’re only looking to work on the hip hinge pattern.

This Kid Needs Help

Because many of your athletes and patients have never used this hinging strategy before, many will struggle to perform this task at first. Below are three teaching points to correct the most common mistakes while learning the hip hinge.

1. Not reaching back: Many patients will not seek to reach backwards maximally with their hips. Have them stand one foot away from the wall with the stick on their back and reach backwards until they touch the wall behind them. Once they’ve achieved success with a number of repetitions. Slowly inch them forward and repeat until you’ve found a distance and pattern that enables them to maximally flex their hips while maintaining strict form.

2. Athlete squats instead of hinging: As I previously mentioned, many athletes are unfamiliar with this movement and seek out what they know best. And in this case it’s a knee or quad dominant movement pattern. Stand beside your patient and place your hands or a mat in front of their knees and ask them to perform the motion without touching their knees to your hand.

3. Patient still can’t separate hips from lumbar spine: stand to the front of your patient and while attempting to hinge backwards place fingertips in the creases of their hip prompting them to push their hips backwards towards the wall.

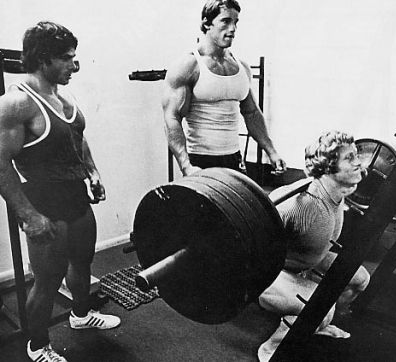

Time for a challenge

After you’ve grooved this pattern again and again and again, it’s time to challenge the pattern under a load. This can be accomplished through the: “Wall Touch – Hip Hinge with KB Pick Up/Put Downs”

1. As before, start your athlete one foot away from a wall (maybe just less in beginners) and have them reach back towards the wall with their butt.

2. Maintain three points of contact with the stick on their head, back and butt crack.

3. Remember: This is not a squat pattern – first motion should be back towards the wall and not downwards.

4. Inch outwards and continue to repeat until distance from wall is appropriate for this patient. Once perfected groove and challenge pattern with kettle bell (KB).

5. Place KB between legs but behind heels. Hip Hinge while reaching down with elbows tightly placed against the rib cage.

6. When grabbing the KB,“crush the handle with your grip”, This will pack your shoulders and engage the lats ensuring a strong back position.

7. Instruct your athlete to stand up as if they have a thousand pounds on the top of their head and they’re pushing it straight up. Finish the movement by squeezing glutes at the end.

8. Beginning athletes may have to prop the KB up on small platform as some will not be able to reach the KB initially. Progress exercise by keeping the KB weight the same and continue to peel away layers from under the KB until KB is on the floor. In the case of a super tall athlete or a patient who is lacking hip mobility, the KB may never get to the ground and thus progression of exercise will include increasing KB weight while maintaining starting height.

Once your athlete has perfected this exercise it’s time to prepare them for high end performance. Remember: never exchange more weight or repetitions for a decrease in technique. Demand perfect form each and every rep.

Progression of Two-Leg Hip Hinge with KB includes:

1. Two hand – one KB

2. One hand – one KB

3. Two hand – two KB

Once you’ve mastered the 2-leg hip hinge, a single leg stance progression is appropriate, and a must for any high level athlete but also important for any low back pain patient since this pattern (golf tee pick up) has a very low compressive load on the spine and a key component in every low back pain rehabilitation.

Continue to groove this pattern then challenge under load with the “Single Leg (SL) Romanian Deadlift (RDL) KB Pick-Up – Put Downs”.

1. Continue to groove this motion with Stick Series as described above.

Progression of the Single-Leg Hip Hinge includes:

1. Two hands – two KB

2. One hand (opposite) – one KB

3. Athlete may need to start with KB’s on boxes or mats as before in order to get down with good technique. Do not rush this movement.

4. ** Instead of doing 1 set of 8 reps think of doing 8 sets of 1 rep. This will ensure that each repetition is perfect and not rushed through.