As the world of physical medicine continues to forge ahead with evidence breakthroughs and paradigm shifts there appears to emerge 3 distinct bodies of clinicians/researchers whom all make very compelling cases why their methodologies are superior for treating patients in pain. Appropriately, a cornerstone of each model is exercise, or better yet, movement. The three ideas:

Biomechanical Model: There is a correct, and incorrect way to move based off of ideal joint alignment and muscle synergies, and once deviations occur improper stresses are placed on nerves, muscles, ligaments and joints, which then cause pain. For the most part, pain is fixed by improving a person’s strength and/or mobility and taking pressure off of said structures. Treatment is guided by evidence using mostly biomechanical assessments and EMG studies to target specific muscles.

Neuromuscular Model: There is a correct and incorrect way to move governed by the central nervous system. Motor patterns developed during childhood represent movement in it’s most natural state and thus are our entryway into restoring proper function of our neuromuscular system. Emphasis is placed upon motor control, proper muscle timing and activation or deactivation of certain muscles. Believes that pain is caused by improper stresses on joints, muscles, nerves and ligaments, but also recognizes the connection between movement and pain in the brain, and changing a person’s movement will change their pain. Treatment utilizes different techniques aimed at restoring proper motor function, with principles grounded in evidence.

Pain Model: There is no perfect way of movement, but rather all movement is good in variability and moderation, and lack of movement is bad. Movement mechanics are largely a construct of westernized medicine and have little relevance to actual pain past the initial insult. Recognizes that improper stresses on joints, muscles, nerves and ligaments cause acute pain, but that pain is always an output from the brain and thus all treatment must be focused on the neuroplasticity of the brain. Changing the brain’s perception of movement will change their pain, and changing a patient’s perception of pain, will change their brain. Treatment is focused on patient education, patient ownership, and the neural tissues of the body.

Why Rehab Works:

My goal is not to push people to subscribe one school of thought since it is likely that they all have their place, but rather to introduce the idea that perhaps when you’re prescribing exercise, it may be working for other reasons than you believe. For example:

Breathing

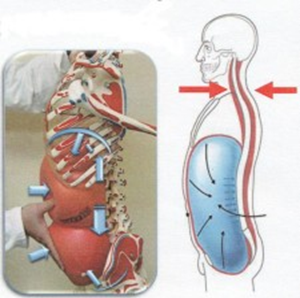

I won’t get into the importance about assessing your patient’s respiratory pattern-there’s an overflow of information coming out on this. But here is why breathing works in all three models:

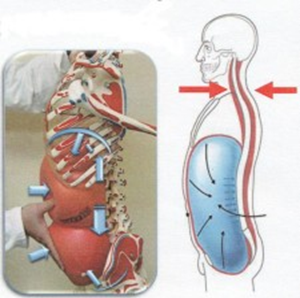

Biomechanical: When properly done full exhalation engages the obliques and pulls the ribcage down into the transverse plane, optimizing its position for respiration and stabilization. According to McGill peak stabilization of the abdominal cavity occurs not at full inhalation, but in the first part of exhalation, or during the weird grunting noise you hear people make as they flirt between squeezing out that last rep or having an aneurysm. It is here that muscles responsible for stabilization of the lower back are working synergistically to prevent shear forces on discs and spinal nerves.

Neuromuscular: One of baby’s first skeletal muscles to ever contract post-partum is the diaphragm. Restoring proper breathing is the very first step in reprogramming motor patterns. Piggybacking the biomechanical model, it is imperative in stabilizing the spine, which becomes the building block for the neurodevelopment of the child. As the child moves through positions in supine, then rolling, then prone etc…the spine stabilizes first in each position before coordinated extremity movements occur. Thus by placing patients into developmental positions and cuing breathing and stabilization, we are bringing motor control back to its most primitive patterns and improving neuromuscular control

Pain: Push play on any meditation series and the very first thing the calm soothing voice whispers to you is to draw attention to your breath. 1) it takes your mind off of anything else you may be thinking of (pain!) and 2) slow deep breaths shift your nervous system from sympathetic to parasympathetic, and we all need some of that. There is a strong positive correlation between anxiety, stress and pain. If we can decrease a patient’s stress, we can decrease their pain. One of the primary methods used with patients in chronic pain is meditation, and the breath is once again the foundation.

Hip Hinges

Biomechanical Model: Improving hip mobility will decrease lumbar mobility, and thus improve lumbar stability. If we move more with our hips, we move less with our back and avoid unnecessary forces on discs, nerves, muscles and tissues. Hip hinging drives glute activation, decreases lumbar flexion, and improve hip flexion. The joint by joint approach suggests a mobile hip and a stabile lumbar spine is the anatomical function of the lumbopelvic complex.

Neuromuscular Model: Have you ever looked at someone’s back and seen two guy-wires running down the sides of their spine, as if they were about to deadlift a car. Only problem is they are just standing.

(Tone much?)

This display of hypertonicity is an indication that there is insufficient activation of the deep stabilizers, and over activation of the global muscles. Likely caused by repetition of movements without proper stabilization, the key to restoring appropriate muscle synergy is to look into motor patterns that are incorrectly recruiting the erectors instead of deep spinal stabilizers. Instructing the patient how to move with their hips as opposed to the lower back avoids perpetuating this faulty motor control, and thus decreases erector activation.

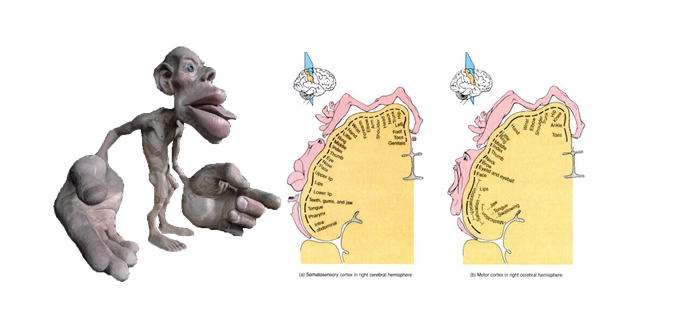

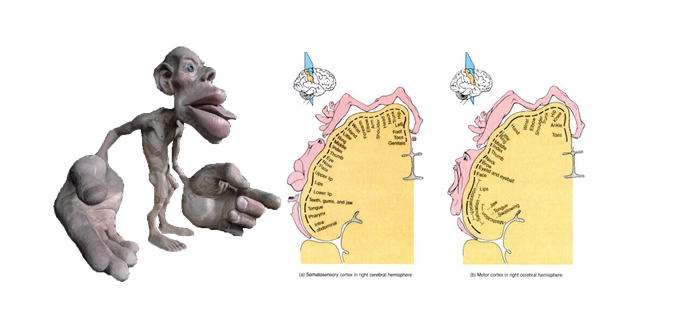

Pain Model: Remember this guy?

Well it appears that he plays a major role in pain patterns, especially in those with chronic pain. Living in the sensory and motor cortices the homunculus is a representation of human body in the brain. Areas of the body with greater fine movement and sensation have larger real estate in the brain, such as the thumb and the mouth. In the presence of back pain, the back’s representation can grow and which causes unassociated movements to become lumped in with back pain. Movement therapy focused on painless specific movements will better define the cortical borders of one body part from another, and may help dissociate hip movement from back movement and therefore back pain.

There are plenty more examples that would elucidate the concept that exercise/movement “works” on various levels.

Bird Dogs:

Biomechanical: Core stabilization training

Neuromuscular: Crawling pattern for baby

Pain: Movement variability is key to changing pain neurotags, and how often during the day do you get down on your hands and knees and crawl like a baby??

Squats:

Biomechanical: Bigtime strength and mobility exercise

Neuromuscular: A major neurodevelopmental milestone

Pain: Lots of LE movement mapping

So next time you prescribe an exercise think to yourself: Am I doing what I think I’m doing?

Chris Joyce is a physical therapist at a sports orthopedic clinic in Boston. He’s currently completing a Sports Residency at Northeastern University, and can be reached at cjoyce@sportsandpt.com.