Still Stretching the IT Band?

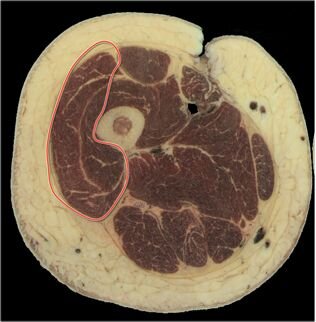

"Our anatomical findings confirmed that the ITB is in fact a thickening of the facia lata, which completely envelopes the leg. In all cases it was connected to the femur along the linea aspera from the greater tronchanter (by the intermuscular septum) to, and including, the lateral epicondyle of the femur by coarse fibrous bands. We failed to demonstrate a bursa interposed between the ITB and distal lateral femur on a single cadaver. The TFL muscle was completely enveloped in fascia, its origin formed by fascia lata arising from the iliac crest. TFL inserted directly into ITB, the latter structure behaving as an elongated tendon insertion of TFL. A substantial portion of Gluteus Maximus inserted directly into ITB, independently of the portion of muscle that inserts into the greater trochanter."

p. 583

“Many of the traditional treatments for ITBS are based on the presence of a bursa between the ITB and the LFC, an ability to stretch the ITB, and the development of friction between the ITB and the LFC due to transverse motion. Our findings challenge these anatomical and pathological principles. Two of the common treatments of ITBS focus on treating local inflammation of the distal ITB and putative ‘‘bursa’’ and stretching the ITB (Noble, 1980; Barber & Sutker, 1992; Fredericson & Weir, 2006). The effectiveness of these two modalities should be questioned given the lack of support for the presence of a lateral bursa and the low magnitude and disparate strain occurring during stretching and MVC found in this study. In regard to treatment of the ‘‘bursa’’ this routinely utilizes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroid injection in the belief that a bursitis or local inflammation is the basis of the condition (Barber & Sutker, 1992). Our gross anatomical studies failed to demonstrate a bursa interposed between the ITB and distal lateral femur on a single cadaver. These findings correlate closely with the works of Fairclough et al. (2006, 2007), who have suggested that a richly innervated and vascularised loose connective tissue (containing pressure-sensing pacinian corpuscles), represents the pain generating structure in the area. This is also suggested by the surgical specimens and imaging findings previously discussed (Orava et al., 1991; Nishimura et al., 1997). Local inflammation in the area may be related to compression of this connective tissue (Fairclough et al., 2006).”

p. 585

“Our anatomical studies also highlighted some important structural characteristics central to understanding the difficulties in stretching the ITB. The longitudinal and firm attachment (0.3mm average thickness) of the ITB to the full length of the femur means that the potential for physiological lengthening is limited. This would appear at odds with a number of authors, which have stretched (Yinen, 1997; Fredericson et al., 2002), and even quantified, the lengthening of the ITB (Fredericson et al., 2002). This is likely to represent an apparent, rather than true lengthening, related to the lengthening of TFL rather than the ITB itself.”

p. 585

Falvey EC, et al. Iliotibial band syndrome: an examination of the evidence behind a number of treatment options. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010:20:580-587.

Registration for the 2014 BSMPG Summer Seminar opens January 1, 2014

BSMPG: Where Leaders Learn