by Art Horne

As we mentioned last week, our society has clearly become hip flexion dominant.

This is really no surprised as Janda identified this “epidemic” long ago and termed it, the Lower Crossed Syndrome. Clearly ahead of his time, and well before Blackberrys and IPhones caused us to hunch over and run into people on the sidewalk, Janda also described and discussed the upper crossed syndrome which is more prevalent today than ever as well. With that said, so many of the young “healthy” athletes that sign up to play collegiate level athletics no longer are able to express the fundamental movement patterns that we so often take for granted. This of course is not always a mobility problem, as many athletes are not able to reach end range of these patterns simply out of a reflexive protective mechanism.

Your body will simply not allow you to go where you have no business going. (Ever wonder why LBP patients can’t touch their toes? Hint: it has nothing to do with hamstring length and everything with your brain not letting you get to end range flexion, you know, the place you have no business going)

In other cases, mobility is the main culprit and can usually be addressed with a simple movement exam along with some corrective therapy and exercises.

Let’s take a look at an example to see what I mean.

Case Presentation:

This athlete presented to me many years ago, and unfortunately the overall theme continues year after year despite our best efforts to educate our athletes and their high school and youth coaches.

Here’s the story:

On evaluation athlete complains of having a persistent anterior hip pain from day one of pre-season practice. She states that she had a “significant” hip injury at age 13 which lasted about one year and limited her from all sporting activities including gymnastics where she originally hurt herself during a coach “assisted” stretch. At the time of the stretch, the athlete’s injured leg was down and extended behind her pelvis, with knee at 90 degrees and the opposite limb forced into extreme flexion. At that time she felt intense pain and was not able to return to any physical activities for about one year.

She went on to a successful high school career and eventually earned a college scholarship for her efforts.

(not the same stretch - but close. OUCH!)

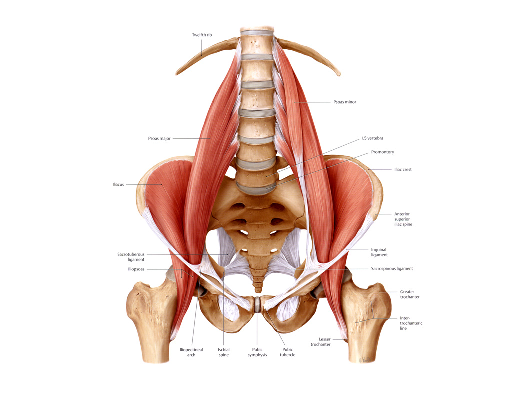

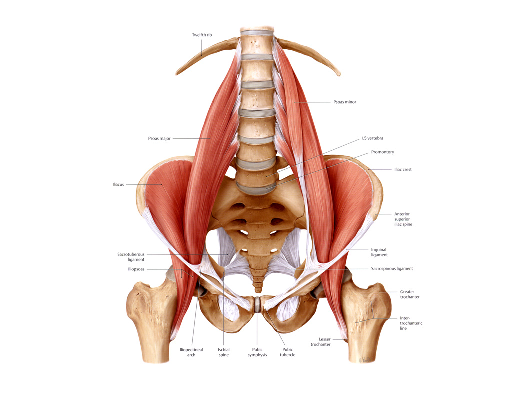

On movement evaluation utilizing the SFMA, cervical and shoulder motions were FN (functional and non-painful), multi-segmental flexion FN, multi-segmental extension FP (functional but painful), multi-segmental rotation DN (dysfunction and non-painful) away from the injured side, single leg stance was DP on injured side, FN on uninjured side (NOTE: during this test athlete complained of pain with standing hip flexion. She was however able to get her knee/femur past 90 degrees of hip flexion but had to first abduct her leg then lift it in front – so to basically avoid iliacus involvement and use only psoas with some help from TFL and Sartorius). Lastly, deep squat was DN.

(Now, according to the SFMA I should have “broke out” her multi-segmental rotation pattern and addressed her subsequent restriction but given her prior history and description of pain I decided to go directly to the prone hip extension test to confirm my suspicion that she had originally injured her iliacus some 5 years ago.)

On prone hip extension, athlete was unable to extend her injured leg to a minimum of 10 degrees.

Treatment Plan: evaluate and address tissue density changes and restrictions within the hip flexion musculature including both psoas and iliacus specifically.

If you aren’t familiar with manual therapy techniques to address soft tissue restriction within the iliacus consult a co-worker or expert in your area for help or training (If you’re in the Boston area one of the most talent manual therapist I’ve ever had the pleasure working with is Dr. Pete Viteritti.

Below are a few key technical points regarding treatment of the Iliacus utilizing a manual therapy release technique. Remember: the iliacus is to hip dysfunction as the psoas is to lumbar dysfunction.

1. Begin with the patient lying on their side, hip and knee flexed and relaxed.

2. With the contact fingers extended, work the soft contact from the anterior superior iliac spine (above the inguinal ligament) medically onto the iliacus treating from proximal all the way distal to the lesser trochanter. The adhesion can be anywhere in the muscle. Also, be sure to move your hand contact treating medially until you bump into the psoas. The junction of the iliacus and psoas is very important, be sure they are not adhering to one another. (adhesion's between muscles which cause them to adhere to one another is much more of a problem than an adhesion in a muscle itself).

3.The inguinal ligament should also be checked to be sure you can bow it both distal and proximal, as it can adhere to the iliacus underneath it. Find the inguinal ligament at the ASIS and trace it as it moves medially and deep. It is only the lateral aspect of it that comes in contact with the iliacus and can become entrapped.

4. As you begin, be sure to move the mesentary medially and not treat through it. Use care to avoid putting tension on the mesentary as this will not only cause discomfort to the patient, but will significantly limit treatment effectiveness.

5. Once on the tissue, begin to put tension on the tissue superiorly with your inferior hand while the superior hand backs it up.

6. Have the patient extend the hip and knee straight and then extend the hip as far as possible.

Post treatment: Athlete was able to regain full prone hip extension, pain resolved with both single leg stance (athlete was able to lift knee/leg straight up in sagittal plane) and multi-segmental extension pattern. Deep squat pattern improved significantly but was not yet perfect. And most impressive post treatment was the look of shock and excitement on her face.

Whether you’re dealing with a shortened iliacus, a tight psoas major or a restricted rectus femoris (or perhaps even a shortened rectus abdominis thanks to the 2 million crunches you’d done), identifying the global limitation first (an extension pattern in this case), and then referring to an expert or addressing the underlying tissue restricting this pattern yourself before high levels of organized activity begins can mean the difference between weeks of treatment post injury or a few moments of your time prior, during your screening process. Of course identifying the exact limiting factor/tissue/pain generator is the ultimate factor when it comes to whether your treatment will be a success or not.

“So what does this have to do with integrated care? This sounds like a pure sports medicine problem and treatment approach to me.”

Perhaps – but all strength coaches can look at global movement patterns including extension and make the appropriate referrals. Whether it’s during your pre-participation examination or during a simple recheck in the weight room – having all coaches, athletic trainers and therapists understanding the normal parameters of human movement and speaking the same language eliminates the language barrier and allows all parties involved in the care and performance of the student-athlete to be provide a unified care approach to the identified problem. Although many strength coaches won’t be able to apply a manual therapy technique for this identified problem, appropriate strategies within the weight room can certainly maintain this new tissue quality and “cement” this new found range of motion with strength exercises appropriate for the athlete and previous injury.

Although the skill set or specific treatment modality between the two professional groups my vary slightly, the underlying philosophy should not and in this case addressing this extension limitation with whatever tools you are allowed to use will certainly pay dividends at the end of the day.

Next Week: When Not Being Able To Touch Your Toes Is Not A Hamstring Issue