By Art Horne

So often ankle dorsiflexion or should I say a lack thereof, is pointed at as the underlying culprit for a variety of movement impairments … and rightfully so. A lack of true talocrural motion can cause havoc up the chain involving itself in a variety of impairments including anterior tibial pain, patellofemoral pain and general low back pain to only name a few.

However, the actual limiting factor causing this lack of osteokinematic motion may be multi-factorial and if clinicians are hoping to address this limitation over the long haul with permanent change the exact location and tissue responsible for this restriction must be clearly identified and addressed with a specific intervention to match the specific tissue.

With regards to soft tissue restrictions there are only 6 possible structures that can limit this motion, and these are:

1. Soleus

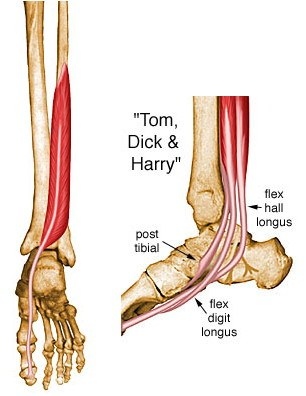

2. Posterior Tibialis

3. Flexor Hallucis Longus

4. Flexor Digitorum Longus

5. Posterior Talofibular ligament

6. Posterior Tibiotalar Ligament

The gastrocnemieus, although probably the very first structure that comes to mind, does not limit true dorsiflexion in function (that is unless you participate in ski jumping or speed walking, and then you need to include this in your assessment), since the knee is almost always flexed when the ankle is asked to express dorsiflexion in function, such as walking, running, squatting, lunging, stepping, jumping and landing.

Now that’s some dorsiflexion!

Remember, in order for your tibia to pass over your talus, and your talus to move between the tibia and the calcaneus we need to think of what pathology or dysfunction is not allowing the above mentioned tissues to lengthen. More often than not, fibrotic adhesions within the muscles or fascial restrictions are to blame, with the filet mignon of tissue treatment choice being an Active Release Technique. Although lesser cuts of treatment choices allow tissues to mobilize at times, rarely can a foam roller or tennis ball address a specific adhesion like a skilled clinician and the appropriate manual release technique. That’s not to say one is wasting their time or shouldn’t employ the soft tissue mobilization techniques that they are allowed to use given their credentialing or state laws, but understanding when to refer to a specialist with a very specific skill set is the difference between a butter knife a ninja – both may get the job done but we all know which one we’d rather have on our side.

So how does one differentiate between these tissues?

Because the Soleus and Posterior Tibialis are the two usual suspects and responsible for the majority of problems when it comes to ankle dorsiflexion limitations, these two will usually require the majority of your focus both in evaluation palpation and treatment.

However, both the Flexor Hallucis Longus and the Flexor Digitorum Longus can limit dorsiflexion and should be excluded to be sure that they are not involved. To exclude these two structures from your list of possible dysfunctional contributors simply ask the patient to maximally dorsiflex their ankle while keeping their heel on the ground.

1. Gently pick up the great toe off the ground into extension. If there is slack and the patient does not indicate an increase in symptoms then the FHL is more than likely not involved.

2. Repeat tissue testing by selecting the toes and pulling them into extension. If there is slack and the patient does not indicate and increase in symptoms then the FDL is more than likely not involved.

To identify the underlying tissue whether it be the soleus or posterior tibialis requires some discernable palpation skills.

Did I make a permanent change?

Charlie Weingroff calls it the “Audit Process” while others such as good friend and colleague Pete Viteritti simply calls it, test-treat-retest. If the correct treatment choice was matched to the correct tissue choice and location then a marked improvement in range, function and/or pain levels should occur.

If minimal or no improvements were made than the following may have occurred:

1. You applied the correct treatment to the wrong tissue (tissue adhesion was within the posterior tibialis and you treated the soleus for example), or

2. You applied the incorrect treatment to the correct tissue (pressure was too light and thus was not sufficient to break up the underlying scar tissue), or

3. The limiting factor was not soft tissue but instead an osteokinematic “misalignment” or a position fault as described and made famous by Brian Mulligan (more Mulligan in a future post).

Summary: The most important step in any treatment approach starts with first identifying the correct pain generator or dysfunctional tissue involved. Without a correct place to start, all treatment options will fail to make a lasting change.