By Art Horne

With recent season ending ACL injuries to New York Knicks Iman Shumpert, and Chicago Bull’s point guard Derrick Rose coming on the same day, (not to mention Eric Maynor from the Thunder and Spanish Star Ricky Rubio earlier this season) discussion has arisen as to how these terrible injuries could have been avoided. Although the possible contributing factors are endless, ranging from previous injury to simply fatigue, one area worth shedding more light on, especially in the case of young Rose, is the implication of the kinetic chain as a whole.

Let’s start at the ground and work our way up.

I think we’d all agree that the big toe is a big deal. But how closely are we looking at this “pivotal” body-ground juncture?

In a study by Munuera et al, researchers found that “Hallux interphalangeal joint dorsiflexion was greater in feet with hallux limitus than in normal feet. There was a strong inverse correlation between first metatarsophalangeal joint dorsiflexion and hallux interphalangeal joint dorsiflexion.” (Munuera et al, 2012).

TRANSLATION: People with abnormally stiff or limited motion at the great toe had excessive motion at the joint just distal.

If you don’t have mobility where you need it, you’ll surely get it somewhere else.

Let’s move up the chain shall we?

In a study by Van Gheluwe and his group, researchers looked at how a stiff or limited great toe joint changes the way we walk. In their study, “two populations of 19 subjects each, one with hallux limitus and the other free of functional abnormalities, were asked to walk at their preferred speed while plantar foot pressures were recorded along with three-dimensional foot kinematics. The presence of hallux limitus, structural or functional, caused peak plantar pressure under the hallux to build up significantly more and at a faster rate than under the first metatarsal head. Additional discriminators for hallux limitus were peak dorsiflexion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint, time to this peak value, peak pressure ratios of the first metatarsal head and the more lateral metatarsal heads, and time to maximal pressure under the fourth and fifth metatarsal heads. Finally, in approximately 20% of the subjects, with and without hallux limitus, midtarsal pronation occurred after heel lift, validating the claim that retrograde midtarsal pronation does occur.”

TRANSLATION: if you have a limited motion in your great toe, pressure changes will occur – increase pressure changes will cause pain over time (think blister on your foot).

And pain changes the way we move – period.

Let’s take a look at the ankle.

In an article by Denegar et al, the authors outline the importance of regaining normal talocrural joint arthrokinematics following an ankle injury. The authors note,

“All of the athletes we studied had completed a rehabilitation program as directed by their physician under the supervision of a certified athletic trainer, and had returned to sports participation. Furthermore, all had performed some form of heel-cord stretching. None, however, had received joint mobilization of the talocrural complex. Despite the return to sports and evidence of restoration in dorsiflexion range of motion, there was restriction of posterior talar mobility in most of the injured ankles. Posterior talar mobilization shortens the time required to restore dorsiflexion range and a normal gait. Without proper talar mobilization, dorsiflexion range of motion may be restored through excessive stretching of the plantar flexors, excessive motion at surrounding joints, or forced to occur through an abnormal axis of rotation at the talocrural joint.” (pg. 172)

TRANSLATION: I repeat, Without proper talar mobilization, dorsiflexion range of motion may be restored through excessive stretching of the plantar flexors, excessive motion at surrounding joints, or forced to occur through an abnormal axis of rotation at the talocrural joint.” (pg. 172)

If you don’t have normal ankle motion, and specifically at the talus, your ankle motion (although appearing normal) is probably coming from other joints and/or in a combination with foot pronation.

Foot Pronation = Tibial Internal Rotation

Tibial Internal Rotation = Femoral Internal Rotation

Tibia and Femur Internal Rotation = Knee Valgus (or knee collapse)

Knee Valgus = BAD

But just because you have some extra motion doesn’t mean you’re doomed right?

No.

But, excessive motion without the ability to control that motion certainly does. So where does knee control come from? The Hip!

But hip strength, control, and neuromuscular timing is seldom appreciated, and in the case of the basketball athlete it is certainly poorly measured, especially after ankle injury.

In a study by Bullock-Saxton, researchers investigated muscle activation during hip extension after ankle sprain and showed a changes in timing of muscle activation in the ankle sprain grouped compared to the non-injured group.

“the results highlight the importance of the clinician’s paying attention to function of muscles around the joints separated from the site of injury. Significant delay of entry of the gluteus maximus muscle into the hip extension pattern is of special concern, as it has been proposed by Janda that the early activation of this muscle provides appropriate stability to the pelvis in such functional activities as gait.” (pg. 333)

In another study examining ipsilateral hip strength/weakness after the classic ankle sprain, researchers demonstrated that subjects with unilateral chronic ankle sprains had weaker hip abduction strength and less plantar flexion range of motion on the involved sides (Friel et al., 2006)

“Our findings of weaker hip abductors in the involved limb of people with chronic ankle sprains supports this view of a potential chronic loss of stability throughout the kinetic chain or compensations by the involved limb, thus contributing to repeat injury at the ankle.” (pg. 76)

“If the firing, recruitment, and strength of the hip abductor muscles in people with ankle sprains have been altered because of the distal injury, the frontal-plane stability normally supplied by this muscle is lacking, and the risk for repeat injury increases. Weak hip abductors are unable to counteract the lateral sway, and an injury to the ankle may ensue.”

TRANSLATION: Ankle sprains cause neuromuscular changes up the chain and specifically in the hip. If this weakness is not addressed after an ankle injury,” frontal-plane stability normally supplied by this muscle is lacking.”

Lack of frontal-plane stability + Knee Valgus = Injury

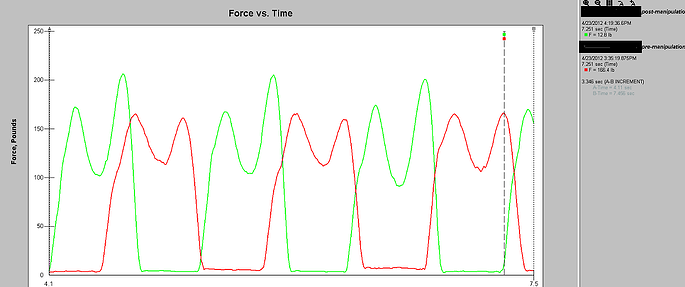

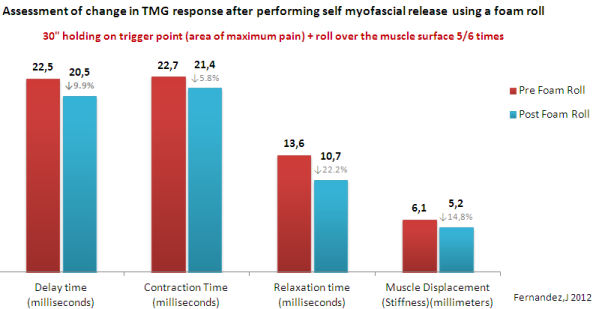

Of course suggesting that the above points are exactly the reason for which Rose suffered his injury is certainly a stretch and not the intention of this post, nor is it to question the treatment that he or any other NBA player received prior to their devastating injury (for the record, the Chicago Bulls Sports Medicine and Strength Staff are regarded as one of the very best in the league). What I am suggesting however is that examining athletes and patients with the use of advanced technology to determine a state of readiness to participate, and/or examine more closely changes in gait and neuromuscular firing is certainly worth pursuing, especially in light of the ever-rising salaries within professional sports. A quick look is certainly worth the small investment.

One thing is for sure, ACL injury is not limited to teenage females or only seen on the soccer pitch.

Previous Posts:

The NBA Should Have Learned From The NFL - Injuries On The Rise

Did The NBA Lock-out Ultimately End Chauncey Billups' Career?

See lectures directly related to gait, injury prevention, and performance at the 2012 BSMPG Summer Seminar:

1. Dr. Bruce Williams: Hit the ground running: Appreciating the importance of foot strike in NBA injuries

2. Dr. Bruce Williams: Breakout Session: Restoring Gait with evidence based medicine

3. Art Horne and Dr. Pete Viteritti: Improving Health & Performance - Restoring ankle dorsiflexion utilizing a manual therapy approach

4. Dr. Tim Morgan: Biomechanics and Theories of Human Gait: Therpeutic and Training Considerations

5. Jose Fernandez: Advanced Player Monitoring for Injury Reduction

See the most advanced player monitoring equipment currently available at the 2012 BSMPG Summer Seminar:

References:

Munuera PV, Trujillo P, Guiza L, Guiza I. Hallux Interphalangeal Joint Range of Motion in Feet with and Without Limited First Metatarsophalangeal Joint Dorsiflexion. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 102(1): 47-53, 2012.

Denegar, C., Hertel, J., Fonesca, J. The Effect of Lateral Ankle Sprain on Dorsiflexion Range of Motion, Posterior Talar Glide, and Joint Laxity. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002; 32(4):166-173.

Van Gheluwe B, Dananberg HJ, Hagman F, Vanstaen K. Effects of Hallux Limitus on Plantar Foot Pressure and Foot Kinematics During Walking. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 96(5): 428-436, 2006.

Bullock-Saxton, J. E., Janda, V., & Bullock, M. I. (1994) The Influence of Ankle Sprain Injury on Muscle

Activation during Hip Extension. Int. J. Sports Med. Vol. 15 No. 6, 330-334.

Friel, K., McLean, N., Myers, C., & Caceres, M. (2006). Ipsilateral Hip Abductor Weakness After Inversion

Ankle Sprain. Journal of Athletic Training. Vol. 41 No.1, 74-78

Smith RW, Reischl SF. Treatment of ankle sprains in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14:465-471.